McLean Asylum for the Insane and St. Elizabeths were two very different, yet for the most part, well-regulated insane asylums (see last two posts). And though they differed from each other in terms of funding and client base, they contrasted even more sharply with the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians. The Canton asylum was a government-funded asylum like St. Elizabeths, and both of these institutions focused on either indigent patients or those of moderate income. What really set the Canton asylum apart from McLean and St. Elizabeths, though, was the difference in oversight.

At McLean, trustees watched over the management of the asylum and a Visiting Committee “made it a point to see personally each patient in the asylum once a week, checking his name off a prepared list,” according to the editors of The Institutional Care of the Insane in the U.S.A. and Canada, published in 1916. This extraordinary degree of oversight took place well before 1900, when the facility had one nurse for every four patients. As the asylum grew, trustees could not keep to the same schedule, but they were still intensely involved with the asylum. Even at the turn of the twentieth century, trustees hired eminent architects for additional buildings, and doctors knew their patients and kept detailed histories on them.

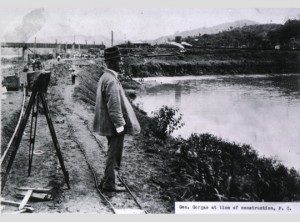

The government hospital, St. Elizabeths, first fell under the scrutiny of a five-member board of charities, appointed by the President of the United States for terms of three years. Additionally, the President appointed a nine-member Board of Visitors. This board included representatives of the military and clergy, and many times included an acting or retired surgeon-general. In 1914, Brigadier General George M. Sternberg, a pioneer in battlefield wound treatment during the Civil War, was President of the Board, and the surgeon generals of the Navy and Army were also represented. The latter surgeon-general was William C. Gorgas, who had been responsible for wiping out yellow fever in Havana after Walter Reed’s discovery of the mosquito vector for it. Though St. Elizabeths had its share of detractors and investigations, that asylum and McLean were typically watched over by prominent locals who took their duties seriously and felt responsible for providing area patients with quality care.

In my next post, I will discuss oversight for the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians.

William C. Gorgas at the Time of the Panama Canal Construction, courtesy National Library of Medicine

______________________________________________________________________________________