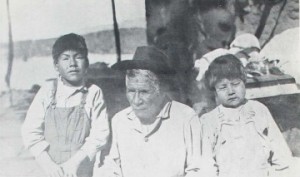

The Bureau of Indian Affairs tried to address the many health issues developing among tribes who had lost their traditional lands, lifestyles, and occupations. However, funds were always far too short to do much good, and healthcare was not provided with any kind of continuity. As time went on and the country began to use surveys and statistics as a basis for action, the government surveyed reservations and schools to discover the extent of the sanitation and health issues which were being reported. When President Taft received the information, which showed a high incidence of tuberculosis and trachoma (an eye disease which often led to blindness), along with a scarcity of medical care, he was shocked.

“The death rate of the Indian country is 35 per thousand as compared with 15 per thousand–the average death rate of the United States as a whole . . .,” he told Congress in 1911. “Last year, of 42,000 Indians examined for disease, over 16 percent of them had trachoma . . . . Of the 40,000 Indians examined, 6,000 had tuberculosis.” Taft asked Congress for more money to go toward Indian health care. . . . “It is our immediate duty to give the race a fair chance for an unmaimed birth, healthy childhood, and a physically efficient maturity.”

Appropriations for Indian medical service rose from $40,000 in 1911 to $350,000 in 1918.

A Grandfather and Two of His Grandchildren Infected With Trachoma, Rincon Reservation, Californina in 1912, courtesy National Library of Medicine

Group Picture at the Phoenix Indian School Tuberculosis Sanitorium Phoenix, AZ, circa 1890-1910, courtesy National Institutes of Health

______________________________________________________________________________________