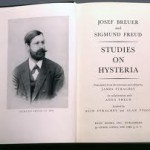

Some Ocular Manifestations of Hysteria, Walter Baer Weidler, 1912, courtesy Wellcome Institute Library

As Freud and other medical men tried to delve into the treatment of insanity (see last post), another group of experts had already made inroads into the blossoming field of early psychiatry. Asylum superintendents were mainly concerned with the management of asylums and how they could help patients within asylum walls. Though treatment in the early years of asylum reform recommended that patients have regular talks with knowledgeable physicians, overcrowded facilities eventually made that impossible. Superintendents had to focus on how schedules, work, and medicine–within the confines of the asylum community–could best be used for patients’ treatment and management.

Some physicians believed that insanity arose from problems within the nervous system. They were confident that study and research would develop new treatments for insanity that would be much better than the care most patients received in asylums. These new doctors were called neurologists. Eighteen neurologists in the U.S. formed the American Neurological Association in 1875, and used the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease as its mouthpiece. They focused on scientific methods and discoveries, versus the sometimes nebulous criteria old-school alienists used as a basis for diagnosis and treatment.

In an article in the March, 1902 issue of the Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, author F. Savary Pearce discussed a case of hysteria in a 17-year-old girl. She had stopped eating, believed that x-rays were being used upon her, and that “blood had been taken from her head and that her head had been ‘sewed up’.” The doctor caring for her isolated her from her family, force-fed her through a stomach feeding tube, and gave her static electricity treatments and massage.

She apparently improved greatly under this treatment, which was not much different (if at all) from what she would have received at an asylum. At the end of his article and after a longer discussion of hysteria and its treatment, Pearce recommended institutionalization for cases which did not clear up within about thirty days, or when patients appeared suicidal.

______________________________________________________________________________________