The Bureau of Indian Affair’s efforts to provide health care to Indians was always hit or miss (see last post). One of the obstacles to providing quality–and timely–care resulted from the vast expanses of land out West. Reservation lands could include acreage that rivaled that of some states, but often only one or two doctors were assigned to cover these huge areas. Even if the Indian population had been in comparatively superb health, doctors’ travel time would have prevented them from seeing many patients. Officials knew that many Indians suffered from serious health problems, but didn’t have the personnel to minister to them effectively.

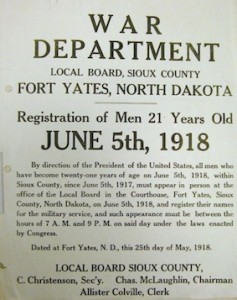

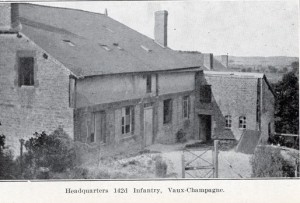

World War I created more problems. Physicians throughout the Indian Service bailed out to work instead for the U.S. Army or to work in the civilian sector; both venues usually meant better pay. The government concentrated most of its construction and supply effort on the army rather than civilian organizations, and there was little done in the way of new construction or even repairs, stateside. Even if the government had wanted to ramp up its efforts to build hospitals and clinics, or provide better health care, it faced the same manpower shortages affecting the rest of the country. Most young, healthy men were overseas or in war-critical positions stateside, and unavailable for more ordinary concerns. Dr. Harry Hummer had such a problem finding and keeping staff at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians that he implored the Indian Office to raise wages so he could fill positions.

Nurse Helen Grace McClelland, Who Served at Base #10 Hospital in France, courtesy University of Pennsylvania

______________________________________________________________________________________