Though TB existed in the pre-Columbian Andean population, there doesn’t seem to be any definitive proof that TB existed in the continental U.S. before Europeans arrived. (Some skeletal remains indicate that it could have existed, however.) What we do know is that explorers and early settlers brought the deadly infection with them, and then spread it to Native Americans. Once Indians were relocated and forced to live on reservations in the 18th and 19th centuries, the disease became much more prevalent.

TB is especially difficult to control when people are crowded together, since the bacteria can live in exhaled breath and transfer to a healthy individual breathing nearby. Crowded reservations and boarding schools became hotbeds of disease, and by the late 1880s, Native Americans had the highest mortality rates from TB ever recorded–ten times the rate of Europeans during their worst epidemics.

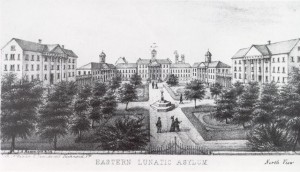

Indian Health Service Nurse Showing X-Ray and Explaining TB Treatment to Members of Navajo Nation, courtesy Library of Congress

______________________________________________________________________________________