Some of the only Canton Asylum for Insane Indians’ patient histories available come from assessments St. Elizabeths staff made when patients were transferred in 1933 (see last two posts). Here is one more sample patient history:

Meda Ensign (Tribe Shoshone)

This patient had been admitted to Canton Asylum in 1913 at age 24, at the request of the Superintendent of Shoshone Agency, Wyoming. Medical certificate states, “Patient was crippled, deaf and dumb and of unsound mind and should be sent to the Insane Asylum for Indians. This girl has no one to look after and care for her and very often runs about in winter weather scantily dressed. She suffers very much from cold and hunger.”

During her residence in Canton she was said to have been quiet, well-behaved, apparently comprehended many things said to her but was unable to articulate words and her actions were those of a young child, showed periods of irritability, times of depression, tried to do some ward work but accomplished very little, was no problem in that she was tidy and clean.

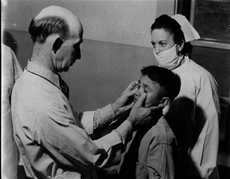

The assessment went on to relate that Ensign had fractured her left leg at one time, and then sustained a second fracture near the first one after slipping on the walk. She also had trachoma (a debilitating eye disease that often led to blindness). Her mental diagnosis was “mental deficiency” or imbecility.

Staff assessment at the time of admission showed that “the patient is quiet, apathetic, disinterested. She appeared quite dully mentally, understood almost nothing that was said to her, could not talk. She was quiet and well-behaved on the ward, neat and tidy in her habits, did not aggravate the other patients or get into fights or show irritability.” St. Elizabeths’ staff also diagnosed Ensign with “imbecility.”