The notion of insanity has been around almost since early cultures recognized that a spectrum of human behavior existed. Ideas about insanity have fluctuated throughout time, however. What was considered aberrant behavior in one era wasn’t considered so abnormal in another, just as so-called “normal” behaviors have changed over time. Continue reading

Tag Archives: Emil Kraepelin

What Do They Say?

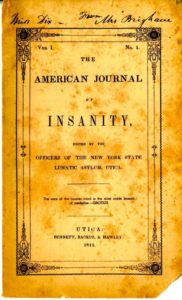

Their own writings provide fascinating insights into the mental health profession’s ever-changing understanding of insanity and how to treat it. Although it was not the only vehicle by which to express current thoughts on the topic, the American Journal of Insanity did have the backing of many authorities in the field. Articles in it ranged from purely practical matters to theoretical speculation concerning the root causes of insanity. My next few posts will give a sampling of what was on the minds of leading alienists in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

In 1863, Dr. John Bucknill wrote an article, “Modes of Death Prevalent Among Insane,” in which he advocated consistency in the way asylum superintendents registered cause of death. Bucknill found that the term exhaustion served as a catchall word that gave little clue as to the actual disease or condition that took a patient’s life. Reading from asylum obituary tables, Bucknill noted that at one asylum a physician attributed 30% of deaths to exhaustion. “In another report, I find a number of deaths attributed to ‘prostration,’ which is perhaps a synonym for exhaustion; while in another report the terms ‘gradual decay’ or ‘general decay’ appear often to be used to express the same facts.”

The vagueness of words like exhaustion and decay kept asylum physicians from keeping accurate records concerning causes of death among their patients. Bucknill urged physicians to give the names of the disease that killed their patients, and then simply add the precise mechanism that shut them down if they wished. Bucknill gave an example of a patient who died from refusing food because of his delusions. Under the system he currently saw, doctors would say the person died of exhaustion, but Bucknill urged, instead: “Let us say that the patient died of acute mania, or acute melancholia, adding, if we think fit, that the mode of death was anemic syncope from refusal of food.”

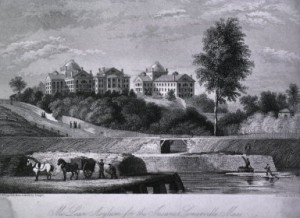

Though Bucknill’s concerns might seem trivial today, he was part of a movement to bring consistency and order to a field which had little science or tradition behind it. Because psychiatry was a new field, early practitioners had to hammer out details on such fundamental issues as how to build insane asylums, what to call them, and then how to classify the illnesses they saw within their walls. Actual therapeutic treatment was then another huge issue.

Religious Melancholia and Convalescence, from John Conolly's book, Physionomy of Insanity, 1858, courtesy Brown University

______________________________________________________________________________________

Opposing Systems

Though Dr. Harry R. Hummer’s medical and psychological experience did not guarantee the best care for patients at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, at least he had the proper background for the position he held. The asylum’s first superintendent, Oscar Gifford, had no medical training at all. The Indian Office bears exceptional fault for appointing someone without the obvious qualifications to head a medical facility; by 1902, it was nearly incomprehensible that an insane asylum superintendent would not also have a psychiatric background.

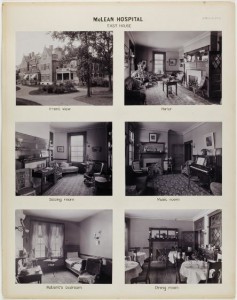

In contrast, the McLean Asylum for the Insane in Massachusetts was a premier establishment that catered to wealthy families who could afford to give their loved ones the best of care. Its staff administered typical therapies for the time: calomel, Epsom salts, opium products, and various purges, along with rest and recreation designed to calm patients and help them keep their minds off their troubles. Recreation could include sewing and reading, billiards, tennis, strolls through manicured gardens, carriage rides, trips into town, and art appreciation classes. But, despite its country club atmosphere, between 1888 and 1892, McLean established laboratories that combined biological chemistry, physiological psychology, and psychiatry, and were perhaps rivaled by only Professor Emil Kraepelin’s laboratory in Heidelberg, Germany.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Continued Futility

As much as Dr. Harry Hummer wanted to expand the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, he was seldom supported simultaneously by all the people he needed to help him. If he could get a commissioner of Indian Affairs on his side, the Secretary of the Interior wouldn’t help him. If he could get a government inspector to recommend expansion, he couldn’t get the commissioner to go along, and so forth. One of the expansion/improvement projects Hummer most wanted was an epileptic cottage. At any given time, approximately 20% of his patients were epileptics, and they created a great deal of work and need for oversight. Hummer wanted to keep all these patients in a dedicated facility to make their care more manageable. In 1922, Chief Medical Inspector, R. E. Newberne, recommended both expansion and an epileptic cottage, saying that additional land could possibly be paid for “from the sale of alfalfa and hogs.” This suggestion surely came from Hummer rather than his own analysis.

At the time of Newberne’s inspection, from a total of 90 patients, 21 had some form of epilepsy, 25 had dementia praecox, (later called schizophrenia by Dr. Emil Kraepelin) and 22 were imbeciles. Hummer also had three patients under 10 years of age, 9 patients between the ages of 10 and 19, and four who were between 70 and 79. Though it would seem that caring for the children and elderly would also be demanding, Hummer did not seem to refer to their special needs when speaking to inspectors or to the commissioner.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Another Player

Emil Kraepelin (1856-1926) led the way for psychiatric research in the nineteenth century. Educated and trained in Germany, Kraepelin studied mental disorders and eventually developed a system of classifying mental illness that took into account a condition’s onset, course, and prognosis.

Kraepelin grouped conditions/illnesses by patterns of symptoms, rather than by the symptoms themselves. He called this a “clinical” rather than “symptomatic” view. Kraepelin’s distinction was important, because almost any single symptom could be seen across a broad spectrum of mental conditions. Classifying by pattern, (or syndrome) rather than symptoms led to a simpler and more uniform diagnostic system.

Kraepelin identified the pathological basis of Alzheimer’s disease, identified schizophrenia (though he named it dementia praecox), and manic depression.

________________________________________________________