The federal government had sought to integrate, or assimilate, Native Americans into the larger white culture for some time before the Canton Asylum opened. Policy-makers did not try to achieve this goal by meeting Native Americans halfway or by gradually introducing them to white values. Instead, their programs tended toward an immersion experience. Children were forced to attend boarding schools where staff tried to cut all ties to their previous cultural experience so they could more easily adopt the white way of life. Continue reading

Tag Archives: Indian boarding schools

Resistance to Boarding Schools

Boarding schools hundreds of miles away from reservations served as a primary tool for the federal government in its attempts to assimilate Native Americans into Anglo culture. By taking children from familiar environments and immersing them into a new one, administrators hoped to break family bonds, alienate children from their cultural pasts, and prevent them from learning native ways from older adults on their reservations.

Of course, parents resisted these efforts. Many refused to give their permission to send children to schools when they had that option; otherwise they hid their children or taught them a “hide and seek” game to play when federal authorities arrived. In turn, authorities were willing to play hardball with the parents. One group of 19 Hopi men were sent to the U.S. military prison on Alcatraz when they refused to give up their children.

Despite their parents’ best efforts, thousands of children were forced to go to boarding schools. Parents were sometimes coerced by threats or the withdrawal of rations into signing permission to allow their children to leave home. Sometimes, however, federal agents actually kidnapped children from their homes.

School and Work

The Indian Office liked to hire Native Americans who had been educated in its boarding school system, figuring that graduates would be more familiar with white American culture than people who had stayed on reservations. Unfortunately, many boarding school educations prepared students for entry level work rather than supervisory positions. Students frequently spent half their school day in manual labor rather than academics, and then worked as servants in white homes during vacations.

Charles Eastman (1858-1939) was an exception to this typical educational path. He attended mission schools and later Beloit (a private college), before graduating from Dartmouth in 1887. He then attended Boston University, graduated in 1889, and became the first Native American with a certified European-type medical degree. Eastman worked in the Indian Health Service within the Bureau of Indian Affairs (known at that time as the Indian Office) and was able to minister to Native Americans casualties at Wounded Knee.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Native Americans And WWI

Many people are familiar with the military contributions of Native American Code Talkers during WWII, but don’t know about Native American contributions to the Great War. Over 17,000 males registered for the draft, but many other men volunteered to enter the military. Data on these volunteers are not as firm, but perhaps half of all Native Americans who enlisted were volunteers. Proportionally, as many or more Native Americans served in the military as other adult American men. Tribal participation rates varied: Oklahoma tribes entered the military at the highest rates, while Navajo and Pueblo men served at the lowest.*

Students from Indian boarding schools like Carlisle volunteered in great numbers, which may have been due both to their familiarity with the military from their school experience as well as a desire to get away from the boarding school environment. Almost without a voice of dissent, whites in authority over these students–all the way up to commissioner of Indian Affairs, Cato Sells–approved of this massive exodus into the military. They attributed it to the success of the Indian Office’s assimilation policy and patriotism on the part of students. Both these factors may have entered into student decisions to enlist, but a thirst for adventure and an equally powerful hatred of their substandard schools were probably just as contributory. Unfortunately, some of these enthusiastic students were underage, with teachers (as the only adults even able to stand in as pseudo-parents) usually turning a blind eye or actually encouraging enlistment.

*Statistics about Native American participation in the military during WWI are taken from Russel Lawrence Barsh’s “American Indians in the Great War; Ethnohistory 38:3 (Summer, 1991).

______________________________________________________________________________________

The Dismal State of American Indians

John Collier wrote an article in 1929, entitled “Amerindians,” which used measured language and concrete statistics to paint a sober picture of American Indians’ well-being. According to Collier’s figures, the number of Indians who lived in the U.S. had fallen from approximately 825,000 at the time of America’s discovery by Europeans, to 350,000 at the time of his writing.

Day school was mandated for children aged six to eighteen, and they had to go to boarding schools away from their families if there were no acceptable schools nearby. Collier noted that “the food allowance for the children is eleven cents a day, supplemented in a few cases by provender from school gardens and dairies.”

The 1925 census showed a 62% increase (28.5 per 1,000) in the death rate of Indians over the previous five years. This figure showed that the Indians’ death rate had surpassed their birth rate. The Bureau of Indian Affairs disputed the census findings, but according to the article, admitted that the Indian death rate was about 95% higher than the general death rate.

________________________________________________________________________

The Problem With Indian Boarding Schools

The Meriam survey took about a year to complete, and team members visited numerous Indian boarding schools. In general, they found schools overcrowded, the food poor, and child labor rampant. The team also observed that, “In a number of schools the girls sleep at night like prisoners with the windows nailed down and the door to the fire escape locked so that by no chance may boys enter or girls leave the building.”

The Meriam Report concluded that government boarding schools acted against the development of wholesome family life. The original intent of the boarding school system was to educate the children and then absorb them into the white population. The absorption plan failed, but family ties were often broken. “Many children today have not seen their parents or brothers and sisters in years,” said the report.

Interestingly, a report written by assistant commissioner of Indian Affairs, Edgar B. Meritt, in 1926 stated: The Indian Bureau is conducting one of the most efficient school systems among the Indians to be found anywhere in the United States or the civilized world.”

________________________________________________________________________

The BIA Field Matron Program

Between 1890 and 1938, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) employed women as Field Matrons. Their job was to go into Native American homes to teach domestic science (sewing, cooking, hygiene, etc.) according to middle-class white standards. This was a relatively peaceful way for the BIA to continue its work of assimilating Indians into white culture; they destroyed Indians’ old habits and ways of doing things and replaced them with the white man’s way.

Matrons taught mainly on reservations, since the feeling was that Indians still living in teepees or roaming the land wouldn’t be able to take advantage of the matrons’ lessons. Besides sewing and other practical accomplishments, matrons taught Indian women to decorate their homes, care for their animals and children like whites, and teach their children sports and Anglo games. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Cato Sells urged matrons to stress the importance of legal marriage to Indians, and to try to increase their desire for material goods so that lazy Indians would work harder to provide them.

Field matrons were charged with “civilizing” Indians in their own homes. Though heavy-handed, it was preferable to tearing families apart and sending children away as the BIA’s boarding school program did. Though the BIA applauded their efforts, eventually devastating health problems among Indians prompted the agency to replace field matrons with nurses.

_______________________________________________________________

Another Pill to Swallow

When Native Americans were forced to live on reservations, their health declined. Poor food quality led to malnutrition and put them at risk for disease and ill health. Two diseases in particular, trachoma and tuberculosis, devastated Indian populations.

Trachoma is an easily transmitted virus that infects the eyes, and is usually picked up in childhood. It thrives in congested, unsanitary conditions, which developed when tribes were crowded together and prevented from moving around and relocating camps. Children would be re-infected so often that scars made the eyelids turn inward, causing the eyelashes to scratch the cornea. Victims said the pain nearly drove them wild, “as though cinders were in both eyes.” Permanent blindness often resulted.

Tuberculosis is a bacterial lung infection that causes death by suffocation from excess fluid (blood or phlegm) or by respiratory failure. Tissue in the lung is killed by TB and eventually the patient simply cannot absorb enough oxygen. By the mid-1800s, the Navajo death rate was ten times the national average. Prior to 1935, most adult TB patients were left to fend for themselves, while children attending boarding schools were either segregated or institutionalized. In 1904, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, William Jones, ordered all infected children out of the schools. Most returned to their reservations and died a slow death.

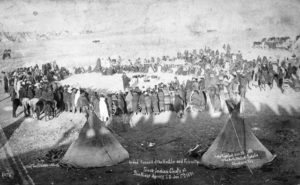

Group Picture at the Tuberculosis Sanitorium, Phoenix Indian School circa 1890-1910, courtesy National Archives

________________________________________________________

A New Life

A host of cruel practices were committed in the name of “civilizing” Indians. Though many children endured a hardscrabble life growing up on reservations, many others went to government boarding schools. Sometimes children were forcibly taken from their parents and put on trains without any preparation for leaving.

When they reached their schools, children were both brainwashed and miserably treated, because boarding schools had a mandate to cut the ties students felt to their homes and families. They were told that their race was inferior to the white race, that their practices were savage, and that even their religion was worthless.

Children were often not allowed to go home to visit their families. The schools were purposely far away from reservations so that it would be a great hardship for families to visit their children. By the time some of the students came home, they had forgotten how to speak their own language.

Boys often wore uniforms and learned to march. Showing homesickness was forbidden. Letters were sometimes intercepted and destroyed or censored. Runaways were a problem, so many children were locked in their rooms at night, or their windows were nailed shut.

Children who conformed to the new way of living were called “good Indians.” Those who resisted, ran away, spoke their native language, or complained were called “bad Indians.”

The Same Three Boys Beginning Civilized Life at Carlisle, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian

_________________________________________________________