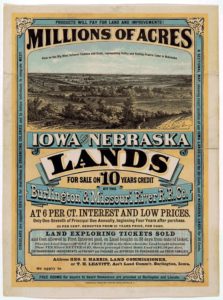

One institution that Canton’s “boosters” hoped would put the town on the map was the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, which was usually called Hiawatha or Hiawatha Asylum by locals. Large asylums for the mentally ill were still the norm across the country, and Hiawatha’s unique patient population seemed to promise renown. Alienists (mental health experts) tended to be very forceful and positive about their field of study, and were eager to add to their knowledge. Town leaders hoped that specialists would come to Canton to study the Indians there, or even conduct their own research.

The facility was smaller than most asylums, but still impressive. It was shaped like a cross, 184 feet long and 144 feet wide, with jasper granite foundations. The outside was of pressed brick with white stone trim on the windows and doors, and inside, a cement-floored basement ran across the entire floorprint. The building had over 100 light fixtures, as well as radiator heat and a modern sewage system. There were also tiled bathrooms and water closets which used range toilets. (This was a unified system which shared a common pipe–toilets flushed at intervals rather than after each use.) Hundreds of trees and bushes were planted on the facility’s acreage, and except for the seven-foot fence around the grounds, nothing indicated that it was a type of prison. Especially for a rural area, Canton’s asylum was a noteworthy structure.

One of the primary reasons the town fought the asylum’s closing was because of the blow it meant to Canton’s economy. During the Depression, the asylum was a reliable source of jobs, and could pay real money for the goods and services it procured. Except for a few local asylum opponents, no one wanted to see the institution shut down.

______________________________________________________________________________________