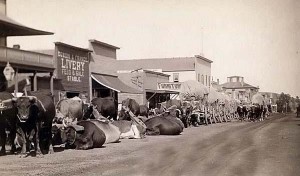

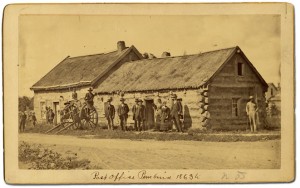

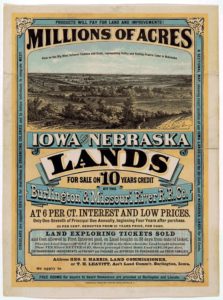

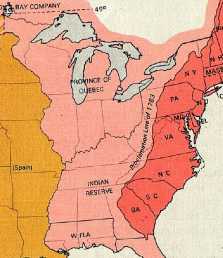

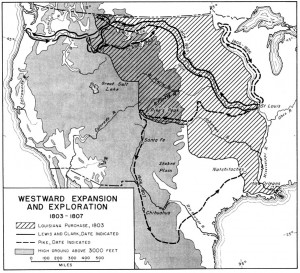

Though it wasn’t officially created until much later, Dakota Territory was carved from land inhabited by the Dakota Sioux and gained through the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. Shortly after the purchase, the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804 established the area’s first permanent American settlement at Fort Pierre. Congress created Dakota Territory in March, 1861. Though Congress quickly reduced its size to that of North and South Dakota, the territory was originally a huge tract of land that eventually became North Dakota, South Dakota, and most of Wyoming and Montana. President Lincoln established a territorial government and appointed his personal physician, William Jayne of Springfield, Illinois as governor in 1861; at that time, the white population stood at only a little over 2,000. Dakota Territory boomed in the 1870s with the discovery of gold in the Black Hills and the expansion of railroads, and by the late 1880s, the territory had almost half a million non-Native American residents. The territory’s population could now justify statehood.

On November 2, 1889, both North and South Dakota were admitted to the United States. There was controversy about which state should be admitted first, and President Benjamin Harrison did not want to show favoritism. He shuffled the Act of Admissions papers for North Dakota and South Dakota, and signed one at random without recording which one it was. Consequently, the two states’ order of admission is listed alphabetically, with North Dakota noted as the 39th state and South Dakota the 40th state.

______________________________________________________________________________________