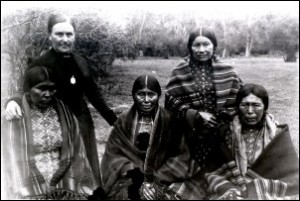

Navajo Code Talkers in WWII have received at least a measure of recognition for their great contributions to that war effort, but the Choctaw Code Talkers of WWI have received far less recognition. In 1917, a group of young Choctaw men began to use their supposedly antiquated and useless language to confound German eavesdroppers. Toward the end of the war when Germans routinely tapped into Allied radio and telephone communications, no code seemed unbreakable. However, Choctaw soldiers in France used their native language to negotiate a troop withdrawal that went undetected by the enemy. That success led to more Choctaw men becoming involved with coded transmissions in their language. Eventually nineteen code talkers contributed immensely to the deception of German eavesdroppers.

Germans were adept at breaking codes, but they had no background for breaking codes based on Native American languages. Traditional military codes were based on European linguistic frameworks, which Native American speakers did not necessarily share. Native Americans didn’t even have words for some essential military terms like “artillery” and “machine guns.” Instead, they called the former “big gun” and the latter “little gun shoot fast.” The Choctaw Nation’s service was highly valuable in turning the tide against Germans during the latter part of WWI.

Ironically, Choctaws (and most other Native Americans) were not U.S. citizens.

______________________________________________________________________________________