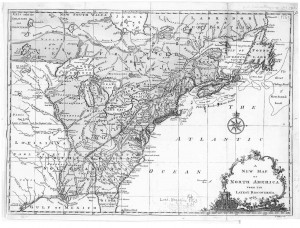

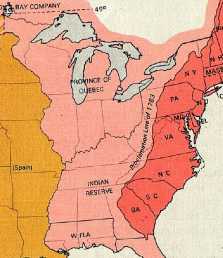

Native Americans were initially a greater threat to colonists than colonists were to them. The British Crown recognized this, and also realized that good relationships were important both to its trade economy and its position with France, which also had big plans for the New World. Around 1755, the Crown placed control of Indian affairs under its own authority rather than the more haphazard arrangements developed by individual colonies. (See last post.) The government established northern and southern departments and appointed a superintendent for each. By 1763, King George issued a Proclamation which established western boundaries which settlers were supposed to respect, and essentially created an “Indian Country.”

After Independence from Britain, America’s Continental Congress also forbade settlement on Indian lands. Congress later made its intentions clear with the Northwest Ordinance of July 13, 1787. The Ordinance stated that: “The utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians, their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress.” The Ordinance added that from time to time, Congress would also make laws to prevent wrongs being done to Indians, and which worked toward friendship and peace.

Leaders of the Continental Congress from a painting by Augustus Tholey, 1894, courtesy Library of Congress

______________________________________________________________________________________