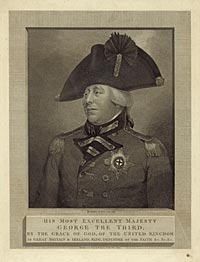

King George III may have been a victim of misdiagnosed insanity–proving that even the highest birth and station could not exempt a person from the faulty reasoning of mad-doctors. When he was 50, King George III began exhibiting bizarre behavior which was perhaps triggered by a case of obstructive jaundice. He experienced hallucinations, fits somewhat like epilepsy, and foamed at the mouth after talking incessant nonsense. Court physicians blistered and purged him, kept him in an unheated room during winter, bound him in a strait jacket, or gagged and tied him to a chair. Dr. Francis Willis, who had experience with mental illness, finally began a course of more humane treatment. The king recovered, but slipped back into three more episodes of mental illness that eventually left him hallucinating and talking to unseen persons and to dead people. He died miserably in 1820, blind and deaf as well as apparently insane.

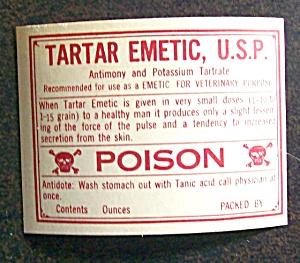

Many researchers have wondered whether or not King George III was actually insane, and evidence seems to lean against it. Though not universally supported, some doctors believe that the king could have had a rare blood disorder called porphyria, which can affect the nervous system. Some of the king’s symptoms indicate the condition, while others do not. One thing that does seem noteworthy is the presence of arsenic in a lock of the king’s hair, analyzed in 2005. Arsenic levels of 1 part per million can result in arsenic poisoning; King George’s hair analysis revealed 17 parts per million. He was probably poisoned through the liberal doses of emetic tartar he received for his varying illnesses, which undoubtedly made all his symptoms of mental illness worse. (At the very least, porphyria is often triggered by the ingestion of heavy metals.) Sadly, the king was often forced or tricked into taking the very medicine that caused or exacerbated his apparent insanity.

______________________________________________________________________________________