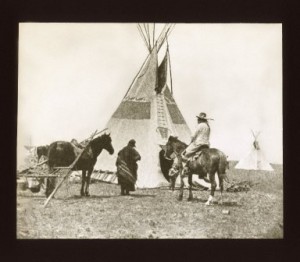

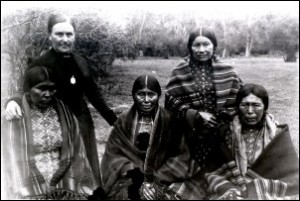

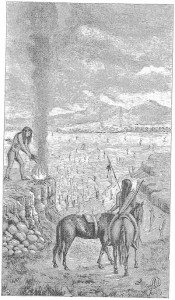

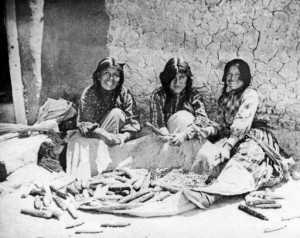

Field researchers found that insanity among Native Americans was rare (see last post) and this finding was backed up by many individual observations over time. In An Account of the History, Manners, and Customs of the Indian Nations written in 1819, the author (John Heckewelder) made several general observations about the way Native American society treated its various members. He found that native peoples treated the elderly with respect and kindness, and with a sense of gratitude for their past sacrifices. “Insanity is not common among the Indians,” Heckewelder went on to say, though he had observed a few instances of it. But, he added, “Men in this situation are always considered as objects of pity. Every one, young and old, feels compassion for their misfortune; to laugh or scoff at them would be considered as a crime, much more so to insult or molest them.”

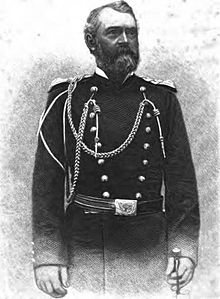

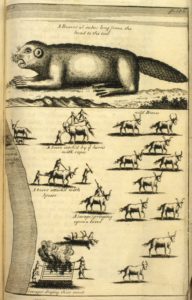

In another book written after the Civil War, Colonel Richard Dodge noted that, “Mental and nervous diseases are rare [among Indians].” Dodge did note that several streams separated by great distances were named after “crazy women” as evidence that Indians did recognize insanity. Generally, however, he found most of the people on the Plains in good health. The closest most came to insanity was when they fell victim to rabies from mad wolves, for which there was no cure.

______________________________________________________________________________________