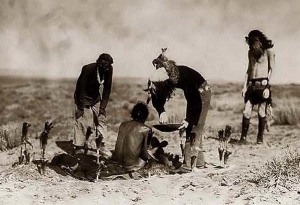

Throughout the ages, people have had to energetically search for food to stay nourished; that task has always been much more difficult in winter. Like most other peoples, Native Americans worked hard to find and preserve enough food for their winter needs. Some game and fish might remain available during the cold months, but not usually in plentiful enough quantities to feed a whole population.

Convenient as these methods are to many of us today, freezing and canning are recent innovations. Napoleon Bonaparte offered a reward in 1795 to anyone who could discover a safe and reliable method to preserve food for his traveling army, and by 1810, both glass “bottling” and true tin “canning” had been invented. Neither of these methods were used by the masses, however, until John Mason invented his glass container with a molded screw-on thread at the top. Until that time and well after, drying, salting, and fermenting foods were the best methods of food preservation for many people.

Native Americans traditionally dried corn, beans, meat, fish, and other common foodstuffs. Food like berries and sweet corn could be sun-dried and eaten later as snacks or with other dishes. Salting and smoking often went together, and were used most often with fish and meat products. Meat (whether salted or unsalted) might be hung in racks over fires fueled by aromatic woods like mesquite or apple wood to both dry and flavor the end product.

Fermented foods like sauerkraut and pickles were not common among Native Americans, though they did eat some fermented foods. A type of Cherokee bread consisted of maize wrapped in corn leaves that then fermented for a couple of weeks; however, it was not a long-term storage item. Fish and meat items might also be allowed to ferment, but again, were eaten fairly quickly after fermentation.