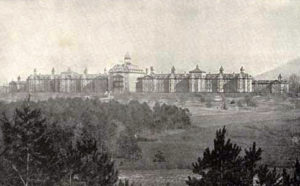

A man suffering from acute melancholia and admitted to Stockton State Mental Asylum (likely in the late 1890s or early 1900s) mentioned that his first noon dinner (lunch) consisted of soup, beans, and potatoes. His 6:00 p.m. supper was only tea and bread. This meager menu was a far cry from the original intentions of asylum founders, who strove to provide nourishing meals to patients as part of their treatment programs.

Farms were usually incorporated into asylum grounds, both to provide fresh produce for patients and staff, and to provide useful “occupational therapy” for able-bodies patients. Superintendents proudly reported the pounds of produce they had raised, as in Dr. Harvey Black’s report for Southwestern Lunatic Asylum (Virginia) at the end of fiscal year 1887. He noted that their gardens had produced 400 bushels of turnips valued at 25 cents/bushel, 12,000 heads of cabbage at 5 cents each, and 62 dozen squash at 15 cents/dozen. Altogether, the gardens produced nearly $2,000 worth of goods for the asylum’s kitchen.

Since the asylum had treated only 162 patients that year, the amount of food grown (Black mentions 16 different crops) probably allowed for a reasonably healthy diet–perhaps better than some patients were able to get at home. Though working on a farm sounds distasteful today, some patients undoubtedly enjoyed it: they got outside, the work was meaningful, and they could both see, share, and enjoy the fruits of their labor.