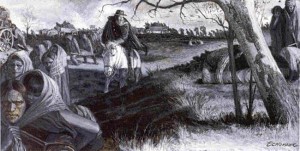

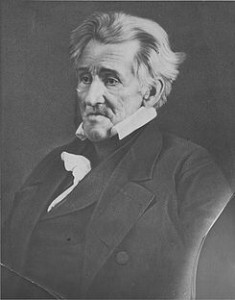

Procession at White Earth Indian Reservation, circa 1908-1916, courtesy Minnesota Historical Society

Because most Native Americans were not U.S. citizens, they had few protections and were often cheated or defrauded of their valuables. In the late 1800s, the Chippewa (also known as Ojibwe) lived on rich woodlands filled with hardwood and pines. These lands were coveted by timber interests,who took advantage of several Congressional acts designed to break up tribal ownership of land.

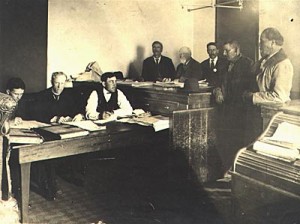

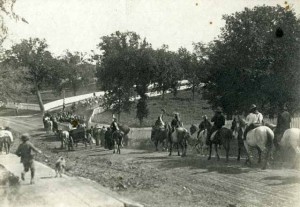

Ojibwe Indians Getting Land Allotments, White Earth Indian Agency, courtesy Minnesota Historical Society Photograph Collection

Through these acts, particularly the Dawes Act (see 7/13/10 post) the Chippewa were each allotted only 80 acres of non-forest land, and told that the government would sell the land they didn’t need to white men, keep the money in the treasury with the Great Father, and give it to them when they needed it.

The allotments were made, and then the non-allotted Indian land was opened up and sold to timber companies, railroads and settlers. Delighted loggers began to clear-cut the forests. As the forests were systematically destroyed, concerned citizens moved to preserve some of the beautiful land that had belonged to the Chippewa. In 1908, Theodore Roosevelt created the Minnesota National Forest, composed of 225,000 acres of Chippewa land which had been lost through the allotment system. The land was renamed the Chippewa National Forest in 1928.

Leech Lake Chippewa Delegation to Washington, 1899

________________________________________________________