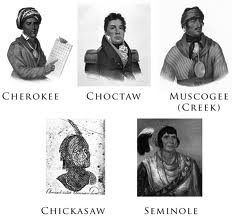

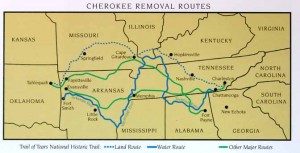

Native Americans were almost continually exploited by the white settlers who relentlessly encroached upon their land. Oil had been discovered in Oklahoma before the turn of the twentieth century, but when deep drilling replaced shallow drilling, oil exploration stepped up in intensity. One result for Indians was a turnover of land ownership that left many of them tenant farmers.

Whites had already gone around protective laws to settle in Indian Territory well before the end of the nineteenth century. By that time, more non-native peoples lived in Indian Territory than Native Americans. Oil made Indian land even more desirable, and several laws were introduced that made it easier for whites to take over desirable real estate. The allotment process, which gave Indians a specified amount of land per head of household, was a first step toward depriving Indians of their property. After allotments were made, any unassigned land (which had previously been part of common tribal holdings) became available for sale to whites. Then, a series of competency laws made it easy for white-dominated courts to determine that certain Indians were not competent to handle their own affairs. Courts often assigned “guardians” to manage Indian land on behalf of their wards. As a result, a huge transfer of wealth took place.

My next post will discuss some guardians’ behavior.

______________________________________________________________________________________