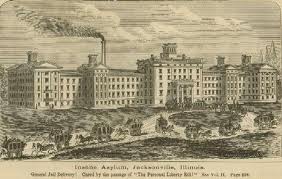

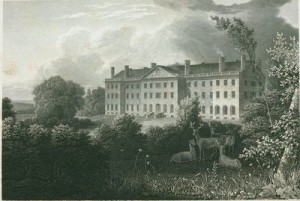

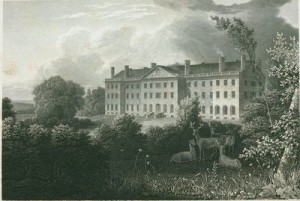

Bloomingdale Insane Asylum

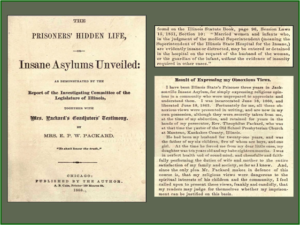

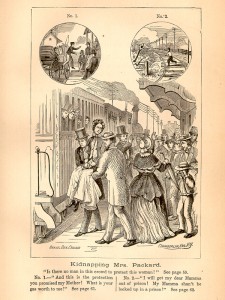

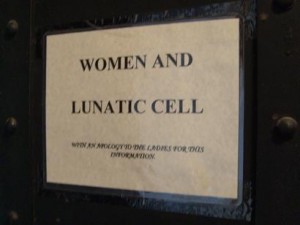

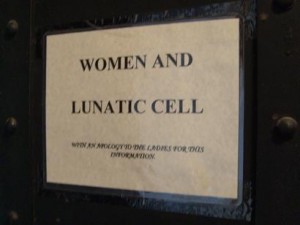

Society has always had to (somehow) accommodate the needs of the insane. In colonial America, families usually supervised members with mental problems, and the community helped as they were able, or tolerated their odd behavior. As people moved into cities and the insane mixed more closely with strangers, authorities began to house the mentally ill in poorhouses or prisons. These spaces were usually dismal and abusive, and many people languished in them for years.

Gonzales County Jail

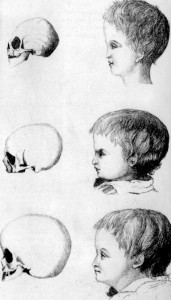

By the 1830s, society began to believe that insanity was something that could be cured, and they sought to decriminalize insanity. Doctors felt that if a person became insane in a home environment, removing that person from home and into a different environment with different routines would be very helpful. Consequently, large institutions became popular by the 1840s.

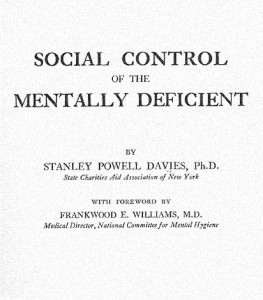

The public was grateful to have a place to send unmanageable family members, and asylums quickly filled. Eventually, they became overcrowded, and doctors realized that many patients simply could not be cured in that kind of environment.

Some critics of asylums argued that patients who were on the way to recovery were surely aggravated, or even set back, by having to associate with patients who were seriously ill. They suggested small cottages with a home-like atmosphere, as a better solution. Huge asylums remained as the only option for many people, though the quality of care declined rapidly. Today, large institutions are no longer popular.

Men's Cottages at Springfield Hospital for the Insane

Cottages at Iona State Hospital

________________________________________________________