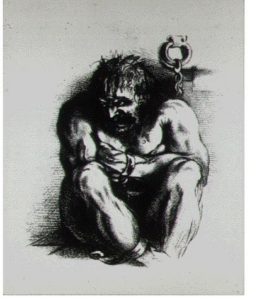

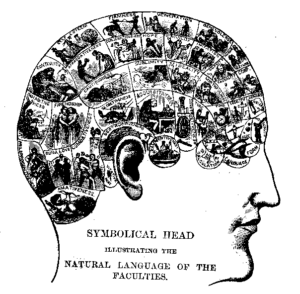

In ancient times, insanity was seen as a result of spiritual forces working against an individual. A god or demon could either inhabit a body and manifest in some way, or merely cause problems for the victim via spiritual power. Sometimes manifestations were considered benign or even holy, and the person who acted oddly was left alone. If the manifestations went against society’s expectations, then the spirit was deemed evil and attempts were made to get rid of it through ceremonies and incantations. Around 460 BC, the Greek physician Hippocrates argued that the brain was the actual organ of the mind and reasoning. Therefore, insanity could be treated just like any other physical problem. His ideas were generally accepted until the Middle Ages, when once again, authorities began to believe that the spiritual realm controlled the mind. During that time, ideas of witchcraft and demonic possession flourished.

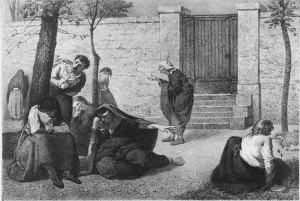

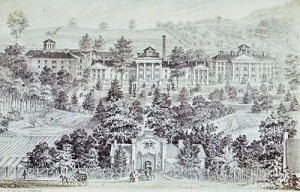

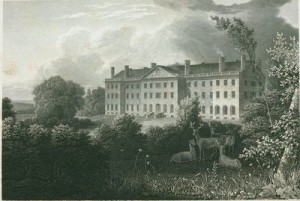

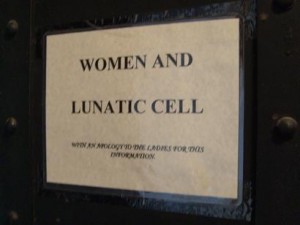

Eventually, Europe once again caught up to ancient Greek thought and began to look at physical causes for mental illness. Because of their evolving beliefs about insanity, European healers stopped dismissing the insane as hopeless cases who should be locked away for life. Instead, they looked for ways to help alleviate what might be just a temporary condition. The insane began to live in asylums rather than prisons and poorhouses, and physicians tried to discover methods of caring for them that would lead to a return of sanity. The early nineteenth century became a very hopeful time in which many doctors believed almost all cases of insanity could be cured.

______________________________________________________________________________________