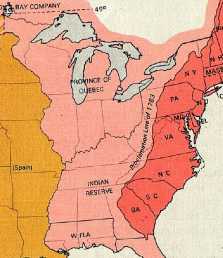

Huge changes took place in the American West during the 1800s. The pre-Revolution colonies were supposed to abide by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which forbade them to move westward past a certain point (called the Proclamation Line) extending from Quebec to West Florida. Colonists resented the restriction and often didn’t obey it, and the Proclamation merely fueled growing aggravations between England and the colonies. Once the American Revolution and the Louisiana Purchase (1803) gave colonists both freedom and land, westward expansion began in earnest.

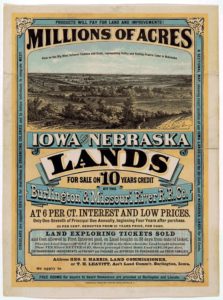

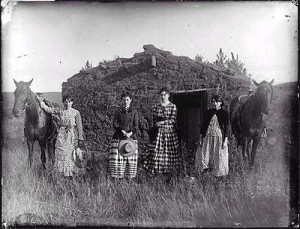

The new country’s own Preemption Act of 1841 allowed squatters on federal land (particularly in Kansas and Nebraska Territories) to buy 160 acres for $200, and then preserve their ownership of the land by making minimal improvements to it or residing on it for about 14 months. Heads of households, citizens or people intending to become naturalized, and single men, could take advantage of this Act. Eastern states tended to oppose the Act because they were afraid their populations would migrate and cause a labor shortage, but were placated when the government agreed to distribute some of the sales money. Later, the Homestead Act (1862) made property acquisition even easier. The Homestead Act allowed any adult citizen or intended citizen, who had never borne arms against the U.S. government, to claim 160 acres of surveyed government land. All a claimant had to do to attain ownership of the acreage was to improve the plot by building a home of some kind on it, and cultivate the land. After 5 years on the land, the original filer was entitled to the property, free and clear, except for a small registration fee. The Act originated during the Civil War, and afterward, Union soldiers could deduct the time they had served from the residency requirements.

The ease of attaining land made westward expansion very attractive, and huge chunks of land were appropriated from Native Americans for use by white settlers. My next post will discuss the settlement of South Dakota, where the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians was located.

______________________________________________________________________________________