Though the minutia of accounting was doubtlessly aggravating (see last post), Dr. Harry Hummer was a penny-pincher who was willing to go beyond the call of duty. Unlike most government employees, Hummer was willing to relinquish part of his funds. Ever zealous to show what an economizer he was, in April of 1921, Hummer offered to return $2,000 from his support fund back to the Indian Office. E. B. Meritt’s reply showed that the Commissioner of Indian Affairs may have been a stickler for accountability, but was not as zealous as Hummer about saving money at the expense of patients: “You are advised that it is not the desire of the Office to withdraw from this fund since the savings, no doubt, can be used to a good advantage in anticipating the future needs of the Hospital. You should therefore make use of the savings in purchasing such items for your future needs as are apparent and making such improvements as are necessary.”

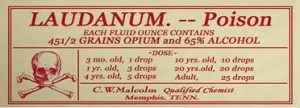

Hummer continued to economize where he could. Like many others in his position, he made use of federal surpluses that the government occasionally offered. In December, 1921, he ordered cathartic compound pills, potassium iodide, aspirin, corrosive mercuric chloride, opium (laudanum), lead acetate, and various other items from the War Department for use at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians. The amount of his order was $16.68.

______________________________________________________________________________________