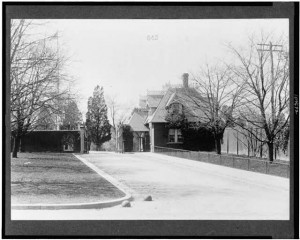

The Canton Asylum for Insane Indians brought plenty of federal money into the local economy. However, as part of the larger Bureau of Indian Affairs, the institution also purchased many of its day-to-day items through governmental suppliers.

In a 1927 letter to the superintendent of the Warehouse for Indian Supplies in Chicago, Illinois, Dr. Harry Hummer requested a couple of staples:

— “Oleomargarine, in 60-lb containers, artificially colored–1600 lbs.” He requested a 60-lb container every two weeks for the fiscal year.

— “Hams, smoked, 600 lbs.” He requested the meat in 200 lb. increments three times a year (November, January, and March). The asylum additionally raised its own cattle and hogs to supplement this order.

Dr. Hummer also bought cots, shoes, and clothing (often excess items that were extremely inexpensive) through federal channels. What he almost never obtained through the government, though, was labor. Attendants, cooks, laborers, etc. were almost always locals, though certain positions like the matron’s (as well as his own) were appointments within the Indian Service.