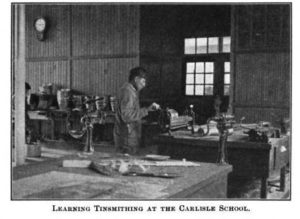

When Dr. Harry Hummer found himself understaffed as a result of the manpower shortage created by WWI, he asked the Indian Office to approve higher wages to help him fill positions. (See last post.) Otherwise, he would have to look at hiring Indian workers. For him, Indian staff was a last resort; for the Indian Service, hiring Native American workers was becoming much more commonplace. One of the most important reasons for hiring Native Americans was the hope that it would make the process of assimilation (submerging Indians into white culture as a way of “killing the Indian” without actual bloodshed) quicker and easier. Indians’ employment within the Indian Service itself seemed a perfect way to give Native Americans a stake in white culture and for them to serve as role models for others on their reservations.

Before the Civil War, not many positions were filled by Native Americans, but the government pushed employment for them after the war. Employment within the Indian Service’s education department went from 15 percent in 1888 to 45 percent in 1899. By 1912, Native American employees made up nearly 30 percent of all regular employees in the Indian Service, not just in its education department. (There aren’t statistics that break down employment in every job category for this period.) Teachers were still mainly white, but the number of Native American teachers had risen from 0 in 1888 to 50 in 1905.

Yakama Indian Employees and School Children, Fort Simcoe, Washington, circa 1888, courtesy Library of Congress

Hospital Staff, Tulalip Indian School, circa 1910, courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection Division

______________________________________________________________________________________