In 1906, Major Charles E. Woodruff, of the Army Medical Corps, wrote an article about nervous disorders and complexion. He believed that excessive exposure to light was responsible for much “nervous damage” to blonds, who didn’t have enough pigmentation to protect themselves in a sunny climate. Proof of this lay in the fact that neurasthenia was more prevalent in the South than in the North.

According to Woodruff, insanity probably followed the same rule. He asserted that “in every part of the world statistics show that the greatest number of cases occur in or near our lightest months–May, June, and July.”

Well-pigmented people, however, were much safer, and didn’t suffer from insanity to the same degree as the “less protected types.” He said that people with dark hair, brown eyes, and olive or brown skin, could “evidently stand mental and nervous strains which blonds cannot endure….”

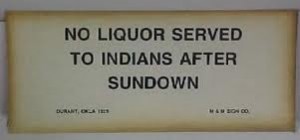

Woodruff’s beliefs were in direct opposition to those who believed Indians had a high prevalence of insanity because of their exposure to civilization.

Hospital for the Insane of the Army and Navy and the District of Columbia, courtesy Library of Congress

________________________________________________________