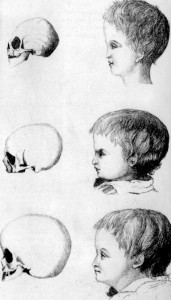

Alienists liked to study groups of insane people like immigrants, men, women, ethnic groups, and it seems especially Indians and Negroes.

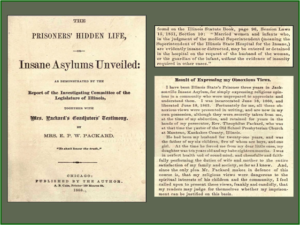

South Carolina was one of the first states to recognize insanity in people of African descent, and passed an act in 1751 “providing for the subsistence of slaves who may become lunaticks while belonging to persons too poor to care for them.” Otherwise, owners were expected to care for any of their slaves who became insane.

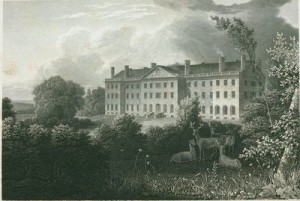

Free blacks were accepted at some insane asylums. The first institution in the U.S. to care for the “colored insane” was the Hospital for the Insane at Williamsburg, VA, which accepted black patients as early as 1744.

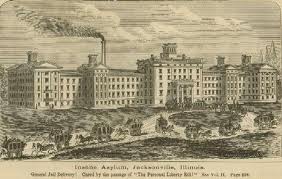

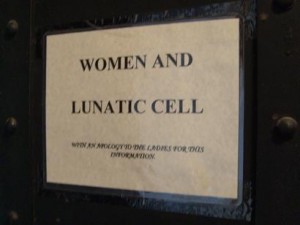

The Western State Hospital for the Insane at Staunton, VA accepted impoverished insane people with “no distinction of race.” The Government Hospital for the Insane (St. Elizabeths) treated insane Negroes in a separate building. Most institutions, if they accepted Negroes, segregated them from whites.

________________________________________________________