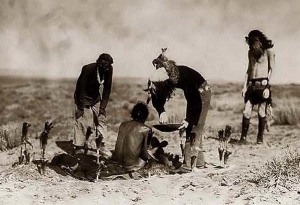

Native Americans believed in ghosts–spirits who were not at peace. This could happen because someone who died had not been at peace, personally. Unrest could also occur because a person was not buried properly or respectfully. Continue reading

Category Archives: Canton Asylum for Insane Indians

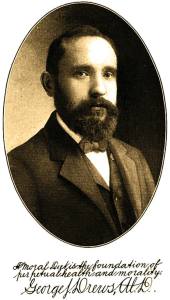

Unfired Foods

As generations move away from them, old ideas become new again. Just as foraging has become popular in the past few years (see last post), so has the idea of eating raw foods. George J. Drews wrote about “unfired food” in 1912 in Unfired Food and Trophotherapy. (Troph simply means “preparing and combining provisions for the unfired diet.”) Continue reading

Native American Harvests

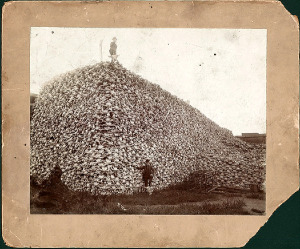

Many people believe buffalo was the primary foodstuff for Native Americans, but that is only a stereotype. Most Native Americans had a bountiful, healthy diet during good years, and preserved food for winter use and bad times. Some tribes grew their own food crops, while others gathered from wild sources.

The “three sisters” is a famous combination planting of squash, beans, and corn in which each crop benefits the other, but Native Americans also ate a wide variety of greens, wild onions, herbs, cactui, nuts and other nutritious foods that were readily available. It is a bit ironic that one of the growing food trends today is foraging for wild edibles.

“Weeds” such as purslane, ramps chickweed, watercress, and dandelions supply nutritious greens to modern diets, while mushrooms have always been treasured gifts of nature. Experienced foragers are welcome lecturers at organic food conferences and similar venues, and books abound on the topic. Foraging appeals to those who want to lessen their carbon footprints, eat organically, add adventure to their food experience, or prepare for a doomsday scenario.

Unfortunately, even this ancient gathering system can create problems in the environment if its practitioners are not careful. Native Americans foraged a wide variety of foods and were careful to leave enough behind to regenerate. Over-enthusiastic gathering today could well play out the way buffalo hunting did, and simply eradicate certain particularly valued wild food. Foraging experts urge newcomers to follow Native American practices of conservation and stewardship so that these wild sources of food remain viable.

Harvest at the Asylum

Non-urban communities had always held the harvest season in high esteem: good crops meant sufficient food for the winter; there was satisfaction in seeing hard work pay off; and perhaps not least, harvest meant an end to the constant labor involved with maintaining a healthy garden. Continue reading

Too Much Change

The federal government had sought to integrate, or assimilate, Native Americans into the larger white culture for some time before the Canton Asylum opened. Policy-makers did not try to achieve this goal by meeting Native Americans halfway or by gradually introducing them to white values. Instead, their programs tended toward an immersion experience. Children were forced to attend boarding schools where staff tried to cut all ties to their previous cultural experience so they could more easily adopt the white way of life. Continue reading

Water Closets

Ordinary homes during the late 1800s and well into the 1900s had few conveniences (see last post); unlike homes today, a dedicated bathroom was a luxury. A largely rural population typically used an outhouse, which could be indifferently built at worst and an uncomfortable distance from the home at best. Continue reading

Oregon’s Insane

Oregon’s settlers initially put the care of the insane up for bid, with the lowest bidder winning the job (as had been the practice much earlier in New England). Eventually, Oregonians petitioned their government for an insane asylum at at time when the territory’s population was only about 14,000. Of that number, approximately five were insane and four were “idiots” requiring care. Continue reading

The Push West

In April, 1750, “Colby Chew and his horse fell down the bank,” wrote Dr. Thomas Walker, an Appalachian explorer, in his journal. “I bled and gave him valatile [sic] drops and he soon recovered.”*

Pioneers going to the West encountered harsh conditions as they moved away from settlement and civilization (see last few posts), but the western frontier itself was an ever changing border. It began in what we would now say was the East, and simply slid westward as the growing population overwhelmed their available land and resources.

Huge Trees Led to Extensive Lumbering in Appalachia, photo circa 1895, courtesy of Shelley Mastran Smith and foresthistory.org

As might be expected, medicine and medical care on these borders were crude and unenlightened, though not much more so than what was seen in cities. Bleeding a patient after a physical injury, as Walker did, sounds counterproductive today but was a common response to almost any illness during Walker’s time.

As each new frontier settled a bit and doctors moved into regions like Appalachia, they brought a variety of experiences, philosophies, and training with them. Doctors were not required to have licenses or even to attend medical school, and they thrived or failed upon the public’s perception of their success. When patients lived through bleeding, dosing with calomel (a toxic compound of mercury chloride), narcotics, and other dangerous concoctions, doctors–rather than the patient’s robust constitution–received credit for the recovery.

* Quoted from Frontier Medicine by Ron McCallister.

An Asylum in South Dakota

The Canton Asylum for Insane Indians was not the state’s first asylum; the Yankton Insane Asylum was established in 1879 during South Dakota’s territorial days. Interestingly, Canton had been considered as a site for that asylum, as well. The Territory had been served by the St. Peter State Hospital in Minnesota before that time, and by 1878, the facility housed 22 patients from Dakota.

The hospital became overcrowded, and Governor William A. Howard was advised that Dakota patients would have to be removed by October of that year. By scrambling for other resources and extending Minnesota’s contract for a few more months, the governor managed to keep the status quo until early 1879.

Frugality and speed were drivers in the effort to relocate Dakota Territory’s mentally ill. Governor Howard wanted to house patients in preexisting buildings within the Territory, but had no luck finding suitable accommodations in Canton, Vermillion, or Elk Point.

Yankton had two large wooden buildings which the governor secured and had rebuilt north of the city for under $2,500. He used his personal funds for the enterprise, for which he was reimbursed in 1880. The territorial legislature was similarly frugal and only appropriated enough money for the patients’ basic needs; real treatment of any kind was not available. In 1899, a fire killed seventeen female patients, and funds were finally appropriated for a more suitable building. By 1909, the institution’s Mead Building followed the norm in insane asylum architecture, and stood out as a beautiful structure.

Going Insane in the West

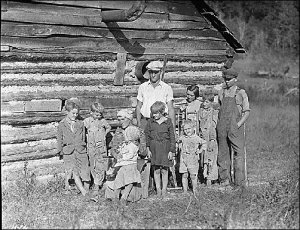

People went West for many reasons, but most carried a dream of creating a better life for themselves in this new, undeveloped territory. Homesteading was advertised as attractively as possible, and though emigrants may have prepared for it physically by bringing as many supplies as they could carry, few were prepared psychologically for the intensity of the pioneer experience.

When they reached the vast stretches of the Great Plains after losing equipment, livestock, and perhaps even family members, it became harder to keep believing the propaganda about new railways, bustling towns, and bountiful harvests–because they were nowhere to be seen.

Loneliness and isolation soon took their toll. Women, especially, seemed to find the West filled with nothing but chores amid all the discomforts of a prairie (sod) home filled with insects, snakes, and ugliness. Men who did not realize their dreams of wealth or farming success could easily become depressed; unremitting stress could impact both genders. Hysteria, melancholia, or “nervous exhaustion,” as well as alcohol abuse and violence could destroy isolated prairie families, who seldom had anywhere to turn for help.

Women seemed to succumb to mental illness more than men, but that may only appear so because women wrote more about what they felt and experienced. Diaries from the trail tell a dismal story of death and privation. From Cecilia McMillen Adams’ 1852 diary:

June 25: Passed seven graves . . .

June 26: Passed eight graves . . .

June 29: Passed ten graves . . .

July 1: Passed eight graves . . .