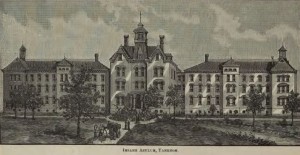

Few people ever wanted to enter an insane asylum, no matter how well run or up-to-date it was. And, like all institutions run by fallible human beings, asylums were not immune to mistakes and misjudgments on the part of their staffs. One problem the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians faced that St. Elizabeths and McLean didn’t (see last few posts) came as direct consequence of its long-distance oversight.

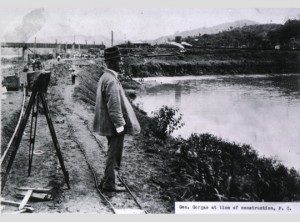

The Canton Asylum for Insane Indians was not under a trustee or board of visitors system like the other two asylums, though it is certainly untrue that this establishment was never inspected or investigated. However, the asylum was managed for the most part from thousands of miles away. The asylum’s superintendent in Canton reported directly to the commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington, DC, and the seven commissioners who held the position during the time the asylum was open very seldom, if ever, actually visited the place.

Agents or inspectors from the Indian Office did come by fairly regularly, but none of these men were psychiatrists. They found it difficult to determine how well the patients were being treated for mental health issues, and usually confined themselves to commenting on the state of the buildings and how efficiently the superintendent ran his farming operation. Medical staff from the Indian Office eventually began visiting much more often as the asylum grew in size and came to the notice of the commissioner through complaints. Dr. Emil Krulish became a frequent visitor and made numerous criticisms that honed in on treatment and the way the superintendent, Dr. Harry Hummer, managed his personnel and patients. However, his voice was ignored and Hummer continued to thrive in his position.

______________________________________________________________________________________