Attendants had a difficult job in any asylum, and the ones at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians were no exception. Besides their special duties when new patients arrived (see last post), they were in charge of general housekeeping on their wards. They were in immediate charge of the nursing of their patients, including the dispensing of medicine and changing surgical dressings. They had to make complete notes about the physical and mental condition of every patient at least once a month.

Attendants were to keep patients comfortable and clean, bathing and changing them as necessary. They had to look after bedding, sweeping, dusting, brightening the floors, hardware, plumbing, fixtures, etc. in their patients’ rooms, as well as clean the lavatories and toilets. Attendants had to accompany patients who could take outdoor exercise, and direct patients in any work tasks they were able to do. Attendants also waited table during meals, submitted a report to the superintendent each morning on any changes in their patients, and accompanied the superintendent and/or physician while he made his rounds.

In 1907, male attendants were paid $480 annually, and female attendants $420. This amounts to $11,500 and $10,100 in today’s dollars, using a Consumer Price Index calculator.

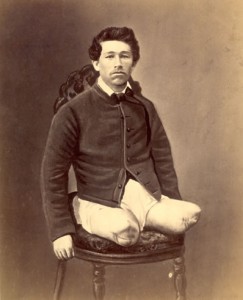

Attendants at Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, circa 1860s, courtesy University of Pennsylvania

______________________________________________________________________________________