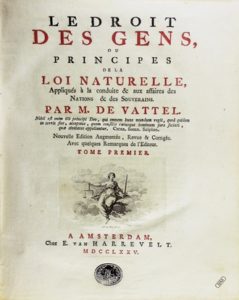

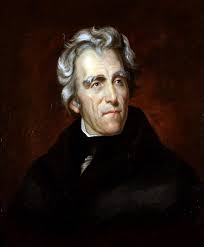

When the U.S. government first dealt with native peoples, its position for the most part was that they were sovereign nations with whom the U.S. needed to negotiate treaties. Once some time had passed and more Europeans crowded into the new land, that position became inconvenient. President Andrew Jackson turned to the reasoning of Emer (or Emmerich) de Vattel (1714 – 1767), who had published The Law of Nations in 1758.

Vattel held the opinion that land use made all the difference. He posed the question: “It is asked if a nation may lawfully take possession of a part of a vast country, in which there are found none but erratic nations, incapable by the smallness of their numbers, to people the whole?” Vattel’s position was that the earth belonged to the human race in general and that “these nations cannot exclusively appropriate for themselves more land than they have occasion for and which they are unable to settle and cultivate.”

This argument suited Jackson, who wanted to set aside land beyond the Mississippi River and force Indians to settle on it so that whites could have the bountiful land Indians currently occupied. This idea of removal was fiercely debated in the press and within Congress, who ordered much of the resulting material printed. More documents seem to have come down against removal, but Congress passed the removal agenda by a small majority in 1830. Supreme Court Chief Justice, John Marshall, disagreed with the action and upheld that Indian tribes possessed their land; he additionally pointed out that official acts of the U.S. involving trade and treaties had already recognized their rights.

Jackson refused to be bound by Marshall’s decision and proceeded with Indian removal through the Act which had been approved in 1830. Among other atrocities, the notorious Trail of Tears resulted.