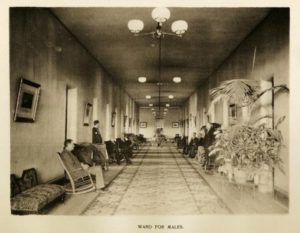

Over a two year period beginning in 1931, Dr. John Maurice Grimes inspected all U.S. institutions caring for the mentally ill. This was done at the request of the American Medical Association. Grimes’ report was so unflattering that he ended up publishing it himself after the AMA withdrew its support. One of the dismaying situations he discovered was how chronic most hospital stays had become. Patients no longer came under care to get well, but to get out of the way of their families.

“The average length of stay of a patient in a state hospital is measured in years,” wrote Grimes. “A patient remaining in a hospital for such a period is not under medical treatment; he is not even under medical observation. …Many of these patients have been practically forgotten by their relatives, and the hospital has made little or no effort to prevent that forgetting or to freshen and strengthen the sense of family obligation.”

Grimes suggested an increase in the number of social workers available to oversee trial “paroles” for patients. The practice of parole or furlough (another common term for visits home) had been adopted by many forward-thinking psychiatrists at the time. The practice served to free up physician time and attention for other patients, and to help the furloughed patient begin to transition back to normalcy. The practice wasn’t as widely adopted as it might have been, because there weren’t enough social workers to help with the process. In some cases, families didn’t really want the burden of caring for their family member again.

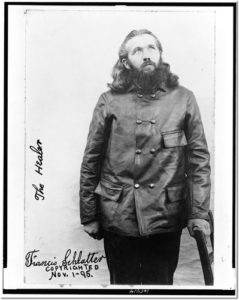

At the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, Dr. Harry Hummer refused to give furloughs. If he thought a patient might relapse, he saw no sense in sending the person home. Unfortunately, there were few cases in which Hummer had complete confidence that a patient had been cured. Though a few patients were discharged, the majority of patients under his care were never allowed home even for short visits. This practice made their homesickness and loneliness much worse.

______________________________________________________________________________________