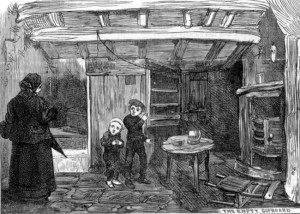

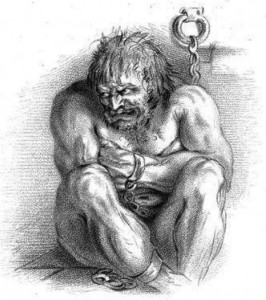

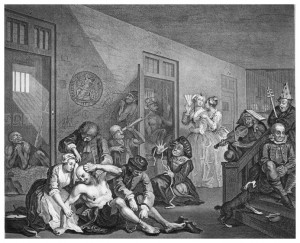

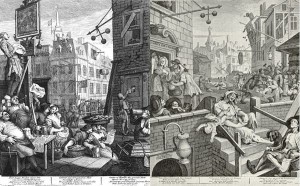

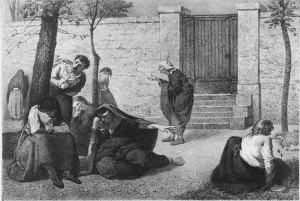

For much of history, dependent persons–children, the sick, poor, elderly, and disabled–were considered the entire responsibility of the family. That family (or probably the head of household) could choose how it wanted to deal with that person and was usually free to act upon its decision. Thus, officials had no reason to interfere if a family sent a six-year-old child off to work ten hours a day, ignored or neglected an elderly parent, or allowed a blind relative to waste away emotionally and intellectually. The poor were often allowed to starve; towns were so anxious not to incur unnecessary expenses that they often banned newcomers who couldn’t prove they had work and could provide for themselves. Independent charities, religious groups, or individuals sometimes offered aid to these dependent groups, but society largely washed its hands of them. Thus, a family member who would not or could not work due to mental problems might be allowed to wander around the countryside as best he could. Violently disturbed members were often chained to prevent their wandering or interference with the rest of the family’s tasks.

This laissez faire treatment of the insane continued into relatively modern times. In Connecticut, for instance, Mary Weed, of Stratford, stated in 1786 “that for 20 years her husband had been so insane as to be kept ‘chained.'” Whether he was chained at home or in a jail is unknown, but one place was as likely as another. Even when towns did try to help dependent citizens, they often wound up in dismal environments. The poor and sick might find a place to stay at an almshouse or workhouse, while an unruly person–no matter what the cause for the behavior–would end up in jail. Eventually, towns were forced to expend more effort to help the helpless, which I will discuss in my next post.

______________________________________________________________________________________