Though President Garfield’s assassin, Guiteau, did not save his life based on an insanity defense, the plea became more common.

In 1924, Dr. William A. White, superintendent of St. Elizabeths Hospital for the Insane, testified in another sensational insanity-plea trial: that of Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb for the kidnapping and murder of a fourteen-year-old boy named Robert Franks. Renowned attorney Clarence Darrow told the court that the two defendants would plead guilty (which they did), and their case subsequently rested upon whether or not they were insane.

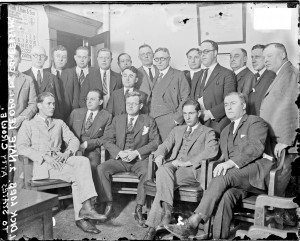

State’s Attorney Robert E. Crowe, Richard Loeb, and Nathan Leopold, Jr., courtesy Chicago Historical Society

Defense attorney Benjamin Bachrach admitted that many times, “the ordinary hearing of insanity in criminal trials, is much in the nature of a vaudeville show.” However, the plea was entered, and Dr. White took the stand in defense of the two young men who had committed such a horrific crime.

The eminent psychiatrist drew a picture of Loeb as someone who had been pushed so hard to achieve that he began to lie about his accomplishments and eventually lost touch with what was true or not. Leopold, White said, had been teased mercilessly as a child, and eventually retreated into a world “where emotion counted for nothing and intellect was all.” White saw both defendants as “trapped inside a world of fantasy.”

Each defendant was sentenced to 99 years in prison for kidnapping, and to confinement in the penitentiary for the remainder of his natural life, for murder. The insanity plea had saved the young men from the death penalty, but not from severe punishment. Loeb died from an assault in prison. Leopold, who had been heavily influenced by Loeb, appeared remorseful in prison; he taught other prisoners, volunteered for malaria testing, and worked in the prison hospital. He was released in 1958 and went to Puerto Rico where he lived a quiet life until he died of the complications of diabetes in 1971.