Native Americans, of course, had recognized and treated various illnesses for many centuries. They relied heavily on herbal knowledge. Herbalists, or herb doctors, received their knowledge about medicinal plants from dreams or visions.

Many healers had a tradition of walking past seven of the desired plants before picking one, so that enough was left for seven generations. They often left offerings in the holes they dug to remove plants, and expressed gratitude to them. Herb doctors tended to specialize in certain illnesses, since their dreams or visions did not generally encompass a wide range of sickness.

Observant healers discovered valuable herbs by trailing sick animals to see what they ate to help themselves. They particularly liked to follow bears, a symbol of healing as well as strength, bravery, and leadership. Herbalists typically studied the effects of the herbs they saw used by animals and experimented with dosages.

Here are how a few herbs were used:

Crane’s bill to stop bleeding.

Golden seal as a tonic.

Horse radish as a diuretic.

Sourwood for indigestion and dyspepsia.

These four examples are for information only and should not be considered safe and effective for actual use. They are taken from The Cherokee Physician, or Indian Guide to Health as Given by Richard Foreman, a Cherokee Physician printed in 1849.

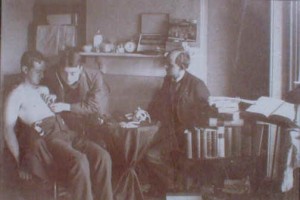

Medicine and Herb Doctor's Sign and Tent, Maricopa County, Arizona (about 1940) courtesy Library of Congress

________________________________________________________