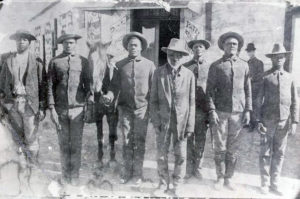

Seminole Negro Indian Scouts, 1889, courtesy NY Library's Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

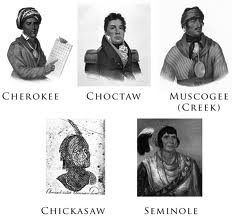

Indian-owned slaves worked hard, but under somewhat different conditions than slaves in the South. Black families were often allowed to live together even if they had different masters, and were seldom broken up. They were allowed to learn to read and write, and slaves who could speak English were valued as interpreters. Though they were clearly owned by their masters, slaves under Indian control were not dehumanized or treated cruelly as a matter of course.

Slavery was still slavery, however, and Indian-owned slaves rebelled against their masters just as they did in the South. Slaves of the Cherokee Nation tried to escape to Mexico in 1842, though they were not successful. In 1850, a band of about 300 Seminoles and black Seminoles were successful in establishing a small free settlement in Mexico that attracted other runaway slaves. Some of the Seminole Indians went back to the U.S., but the black Seminoles remained in Mexico until after the Civil War. By the 1870s, the U.S. Cavalry in Texas accepted black Seminoles into their ranks as Seminole Negro Indian Scouts.

Black Seminole Army Scouts along Mexican Border, circa 1900, courtesy University of Texas, San Antonio

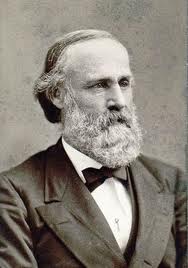

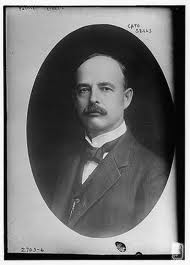

Lt. John Bullis, Commander Seminole Negro Indian Scouts at Ft. Clark, Texas, courtesy Ft. John L. Bullis

________________________________________________________________________