Any reasonably ambitious man could become a doctor during the nation’s early years. Few licensing requirements existed, and men could choose to attend one of many substandard medical schools that were unbelievably slack in their requirements for both entry and graduation. Some men never went to school at all, but either “read” to be a doctor or served as apprentices under a practicing physician until they felt able to go out on their own.

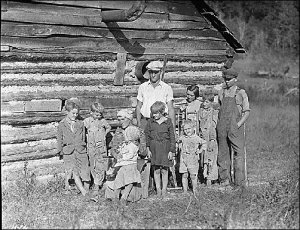

Though some aspiring doctors took these routes to avoid overtaxing themselves mentally or financially, many others simply were not able to “go East” to an established medical school. They studied earnestly–probably harder than many of their college-educated peers. In Appalachia, many doctors took an interest in herbs and local healing folklore, and incorporated this knowledge into their practices.

Because it was so easy to become a doctor, physicians in the early 1800s often saturated their markets to the extent that nearly none of them could earn a real living. (This is one reason that a well-paid superintendency at an insane asylum was initially such a coveted position.)

Physicians moving into Appalachian territory often advertised their services, and sometimes offered testimonials from (supposedly) impartial and healed patients they had helped. Others made money on the side through the sale of medicines, or pulled teeth, preached, or farmed. Many physicians were paid in produce or livestock and found it difficult to actually earn cash.

Despite some undisputed charlatans and incompetents, frontier doctors in Appalachia and elsewhere were incredibly dedicated. Many doctors risked their lives to travel tremendous distances over dangerous terrain to attend patients who might pay them with fresh eggs and produce, or not at all.