In April, 1750, “Colby Chew and his horse fell down the bank,” wrote Dr. Thomas Walker, an Appalachian explorer, in his journal. “I bled and gave him valatile [sic] drops and he soon recovered.”*

Pioneers going to the West encountered harsh conditions as they moved away from settlement and civilization (see last few posts), but the western frontier itself was an ever changing border. It began in what we would now say was the East, and simply slid westward as the growing population overwhelmed their available land and resources.

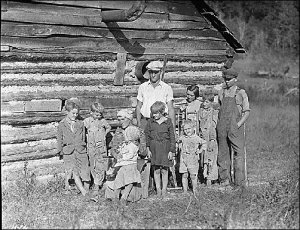

Huge Trees Led to Extensive Lumbering in Appalachia, photo circa 1895, courtesy of Shelley Mastran Smith and foresthistory.org

As might be expected, medicine and medical care on these borders were crude and unenlightened, though not much more so than what was seen in cities. Bleeding a patient after a physical injury, as Walker did, sounds counterproductive today but was a common response to almost any illness during Walker’s time.

As each new frontier settled a bit and doctors moved into regions like Appalachia, they brought a variety of experiences, philosophies, and training with them. Doctors were not required to have licenses or even to attend medical school, and they thrived or failed upon the public’s perception of their success. When patients lived through bleeding, dosing with calomel (a toxic compound of mercury chloride), narcotics, and other dangerous concoctions, doctors–rather than the patient’s robust constitution–received credit for the recovery.

* Quoted from Frontier Medicine by Ron McCallister.