The American diet has been under attack for nearly two centuries, mainly for its fatty, meat-based content. Like George J. Drews and his unfired or raw food diet (see 10/26/14 post), Sylvester Graham advocated a vegetarian diet. Graham’s diet was not quite as strict, however, since he did allow baked whole grains. However, it was a bland diet that didn’t allow spices–not even pepper. Continue reading

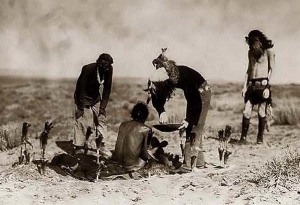

Native American Ghosts

Native Americans believed in ghosts–spirits who were not at peace. This could happen because someone who died had not been at peace, personally. Unrest could also occur because a person was not buried properly or respectfully. Continue reading

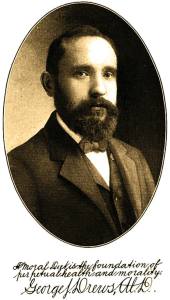

Unfired Foods

As generations move away from them, old ideas become new again. Just as foraging has become popular in the past few years (see last post), so has the idea of eating raw foods. George J. Drews wrote about “unfired food” in 1912 in Unfired Food and Trophotherapy. (Troph simply means “preparing and combining provisions for the unfired diet.”) Continue reading

Native American Harvests

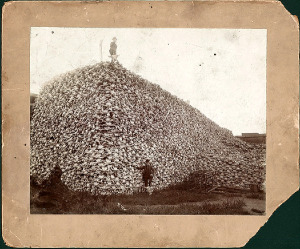

Many people believe buffalo was the primary foodstuff for Native Americans, but that is only a stereotype. Most Native Americans had a bountiful, healthy diet during good years, and preserved food for winter use and bad times. Some tribes grew their own food crops, while others gathered from wild sources.

The “three sisters” is a famous combination planting of squash, beans, and corn in which each crop benefits the other, but Native Americans also ate a wide variety of greens, wild onions, herbs, cactui, nuts and other nutritious foods that were readily available. It is a bit ironic that one of the growing food trends today is foraging for wild edibles.

“Weeds” such as purslane, ramps chickweed, watercress, and dandelions supply nutritious greens to modern diets, while mushrooms have always been treasured gifts of nature. Experienced foragers are welcome lecturers at organic food conferences and similar venues, and books abound on the topic. Foraging appeals to those who want to lessen their carbon footprints, eat organically, add adventure to their food experience, or prepare for a doomsday scenario.

Unfortunately, even this ancient gathering system can create problems in the environment if its practitioners are not careful. Native Americans foraged a wide variety of foods and were careful to leave enough behind to regenerate. Over-enthusiastic gathering today could well play out the way buffalo hunting did, and simply eradicate certain particularly valued wild food. Foraging experts urge newcomers to follow Native American practices of conservation and stewardship so that these wild sources of food remain viable.

Harvest at the Asylum

Non-urban communities had always held the harvest season in high esteem: good crops meant sufficient food for the winter; there was satisfaction in seeing hard work pay off; and perhaps not least, harvest meant an end to the constant labor involved with maintaining a healthy garden. Continue reading

Too Much Change

The federal government had sought to integrate, or assimilate, Native Americans into the larger white culture for some time before the Canton Asylum opened. Policy-makers did not try to achieve this goal by meeting Native Americans halfway or by gradually introducing them to white values. Instead, their programs tended toward an immersion experience. Children were forced to attend boarding schools where staff tried to cut all ties to their previous cultural experience so they could more easily adopt the white way of life. Continue reading

Water Closets

Ordinary homes during the late 1800s and well into the 1900s had few conveniences (see last post); unlike homes today, a dedicated bathroom was a luxury. A largely rural population typically used an outhouse, which could be indifferently built at worst and an uncomfortable distance from the home at best. Continue reading

Sharp Contrasts

Much of the commentary concerning insane asylums tends toward the negative, and rightly so, since they were often places of confinement for people who were in them unwillingly. Treatments were also much too vigorous at times, and many patients must have felt a pervasive sense of potential violence within the institution. Continue reading

In the Long Run

Insane asylums were initially embraced because they held out the hope of curing the insane, rather than merely incarcerating them. Recovery rates were high at first, in the typically small asylums where doctors could devote themselves to patient care and set up individualized plans. Continue reading

Oregon’s Insane

Oregon’s settlers initially put the care of the insane up for bid, with the lowest bidder winning the job (as had been the practice much earlier in New England). Eventually, Oregonians petitioned their government for an insane asylum at at time when the territory’s population was only about 14,000. Of that number, approximately five were insane and four were “idiots” requiring care. Continue reading