Dr. William A. White was an undisputed leader in the field of psychiatry (see last post). He was St. Elizabeths’ superintendent for over twenty years, and implemented many innovations. St. Elizabeths endured its own cycles of overcrowding, scandals, and investigations, but it was generally considered one of the leading institutions of its kind. It attracted some of the country’s best psychiatrists and researchers, who wanted to be affiliated with the asylum and its good reputation. Continue reading

Tag Archives: St. Elizabeths Hospital

More Hardship

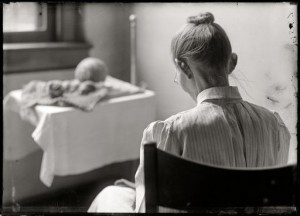

Volunteers at St. Elizabeths Hospital who Worked With Shell Shocked Vets, courtesy George Washington University

Dr. Hummer faced other difficulties associated with the war effort (see last post), particularly a troublesome personnel shortage. He told the commissioner of Indian Affairs that “it is extremely difficult to fill the existing vacancies and I am compelled to keep two or three employees who should be separated.” Since Hummer was typically just fine with a bare-bones staff, his situation at this point was dire; in August, 1918, he had only one male and one female attendant on staff (he should have had three of each). Hummer suggested an increase in pay as a possible solution to his problem, to $40/month with board and lodging for male attendants, and $35/month with board and lodging for females.

A project near and dear to Hummer’s heart also gave way to the war effort: the Indian Office denied his request for an epileptic cottage. This was partly because the asylum still had some vacancies and didn’t seem to need additional rooms. More importantly, as the assistant commissioner of Indian Affairs pointed out, the administration was already in the middle of a huge building program that “will of necessity withdraw carpenters from every section of the country.” Hummer may have been able to counter this with an offer by locals to help with construction, but even he could not argue with E. B. Meritt’s second consideration: there was a need for economy elsewhere in the expenditure of public funds “in order to more successfully prosecute the war.”

Hummer had perhaps anticipated this emphasis on war concerns when he made the following suggestion: “It is possible that the present war will necessitate the construction of another building at this place to care for the insane Indian soldiers or sailors, provided your Office deems this proper.” One way or another, the superintendent wanted additional buildings and patients.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Always Positive

The Sioux Valley News, Canton’s weekly newspaper, was unrelentingly upbeat about Canton and its prize establishments.

When the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians faced closure after two serious investigations, the newspaper decried all attempts to shut the facility down and rallied to the asylum’s cause. Continue reading

Doctors and Nurses

Doctors at insane asylums were recognized authorities in their fields, and most believed they should have total control of their institutions. They expected the utmost deference from staff, including their nurses. Dr. Harry Hummer had many problems with his staff, not only because of his egocentric personality, but also because of his own background and training. He had come from a large institution whose staff interaction was patterned after the etiquette and tradition of the military; he also had servants and “colored” help to whom he could speak as he wished. When he got to the more independent-minded West, his staff resented his high-handedness and bad temper. Some were terrified of Hummer, but others actively spoke against him.

When discontent at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians prompted a thorough inspection, supervisor Charles L. Davis discussed the reasons behind some of Hummer’s problems. “He is fully imbued, as are many others who have never been east [Davis’ error] of the Allegeheny [sic] mountains, that the people of the central west are an uncouth,- ill-mannered and ignorant class.” With this attitude at the ready, Hummer could not help but rub his staff the wrong way.

Davis continued, “He has also evidently been accustomed to speaking to the help about his home and possibly in the hospital where he has served in the manner of master to servant, and has maintained a similar matter of address toward his employees.”

Not much in Hummer’s background and personality boded well for harmony within the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians.

______________________________________________________________________________________

A Long Day

Attendants had a difficult job in any asylum, and the ones at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians were no exception. Besides their special duties when new patients arrived (see last post), they were in charge of general housekeeping on their wards. They were in immediate charge of the nursing of their patients, including the dispensing of medicine and changing surgical dressings. They had to make complete notes about the physical and mental condition of every patient at least once a month.

Attendants were to keep patients comfortable and clean, bathing and changing them as necessary. They had to look after bedding, sweeping, dusting, brightening the floors, hardware, plumbing, fixtures, etc. in their patients’ rooms, as well as clean the lavatories and toilets. Attendants had to accompany patients who could take outdoor exercise, and direct patients in any work tasks they were able to do. Attendants also waited table during meals, submitted a report to the superintendent each morning on any changes in their patients, and accompanied the superintendent and/or physician while he made his rounds.

In 1907, male attendants were paid $480 annually, and female attendants $420. This amounts to $11,500 and $10,100 in today’s dollars, using a Consumer Price Index calculator.

Attendants at Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, circa 1860s, courtesy University of Pennsylvania

______________________________________________________________________________________

St. Elizabeths Superintendents

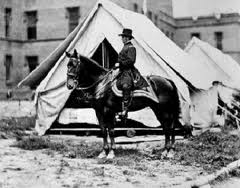

Reformer Dorothea Dix was instrumental in founding St. Elizabeths in Washington DC, as a place for “enlightened curative treatment of the insane of the Army, Navy, and District of Columbia.” She recommended Charles H. Nichols for the position of superintendent. President Millard Fillmore appointed him to that position in 1852.

The hospital was constructed during Nichols’ tenure as superintendent. When the Civil War broke out, Congress authorized the unfinished east wing as a temporary hospital for Union soldiers, and the 60-bed West Lodge was used for sailors in the Potomac and Chesapeake Fleets. General Joseph Hooker was a patient at St. Elizabeths after the battle of Antietam, but was cared for in Dr. Nichols’ quarters.

Dr. Nichols and other male staff rode out to battlefields around the DC area, to treat wounded soldiers. Recuperating patients filled in for them when possible. Not all patients survived, and both Union and Confederate soldiers are buried on the grounds of St. Elizabeths.

Dr. Nichols remained as St. Elizabeths’ superintendent until 1877.

________________________________________________________________________

Insane Vacations

When doctors first began removing patients to asylums, they felt that visits home would be unproductive. They even felt that visits to the asylum by family might not be a good idea, since they could agitate or upset the patient. Sometimes visitors insisted on coming, so asylums usually did have parlors or reception rooms for family visits.

Doctors eventually came to think that visits home might be all right in promising cases, and began to allow what they called furloughs. Patients could go home for 30 days or longer.

Since doctors believed that much of insane behavior was a matter of self-control, they thought furloughs could work in two ways. Either the patient had learned self-control at the institution and could maintain it at home, or the thought of going back to the asylum would be a sufficient motivation for the patient to exercise self-control.

Even though some patients had to return to the asylum, doctors were willing to give them additional chances to go home. That change in attitude undoubtedly meant a lot to patients who were aware of their surroundings and truly trying to get well.

________________________________________________________