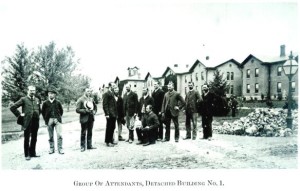

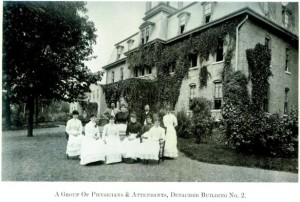

Ward attendants were the backbone of patient care in asylums, and their attitudes and skills could make or break a patient’s experience (see last post). At the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, attendants were never trained and very likely relied on their home experiences with raising children or being around perhaps difficult family members. The stress and tempo of caring for several children at home might mimic some of the tasks of attendants, but it made a difference that attendants were usually dealing with adults rather than children. Carrying a small child to a bath–even an unwilling one–might be stressful, but a parent would prevail. That might not be so true in the asylum setting. Here are just some of the routine tasks male attendants were expected to complete for ten or more patients each day:

— wake patients up (6:00 a.m.) and see that each patient washes his face and hand, and combs his hair

— attend the morning cleaning, bedmaking and tidying of the ward

— see that the lavatories, tubs, toilets and urinals are in good working order and not leaking. Fixtures are to be washed whenever necessary and scrubbed with a cleaning powder at least once daily. All faucets are to be polished whenever necessary

— all wood work is to be rubbed down once daily with an oiled cloth

Willard Asylum Patients Working in the Sewing Room. Structured Activities Made Supervision Easier for Attendants

In addition to these duties, attendants had to take patients to the dining room, feed those who could not feed themselves, bathe and change the clothing (or at least clean and change) patients who soiled themselves, take each able-bodied patient outdoors for exercise at least twice daily, shave them once a week, give them haircuts and trim their nails, and on and on. Patients were always to be supervised, and attendants were never to leave their wards except if duty required. Before doing that, they had to make sure no patient had a lighted pipe or cigarette, etc.

It is little wonder that being an attendant was not an attractive job, and didn’t usually draw people who could get easier work with better pay, elsewhere.