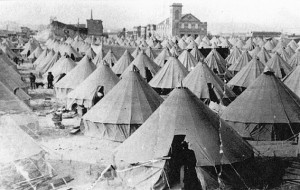

Insane asylums were not just for the poor and friendless. Though they were more typically cared for at home through private physicians and attendants, wealthy people also went to insane asylums. Because they were paying patients, they usually received better food and more attentive care. Here are a few patients who stayed in public insane asylums:

Zelda Fitzgerald, wife of F. Scott Fitzgerald — McClean Asylum

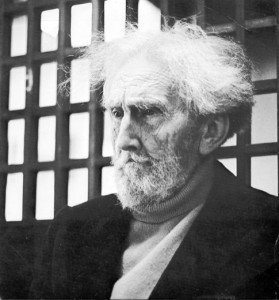

Ezra Pound- poet — St. Elizabeths

Stanley McCormick, family fortune from McCormick harvesting machine — St. Elizabeths

Mary Todd Lincoln, widow of Abraham Lincoln — Bellevue Asylum

Vincent Van Gogh, artist, Saint-Paul-de-Mausole Asylum, Saint Remy, France

Romeo Singer, founder of Singer Sewing Machines — Amityville Insane Asylum

Woody Guthrie, singer — Greystone Park State Hospital

________________________________________________________________________