The Indian Bureau was never culturally sensitive, especially when it came to Native American celebrations. It actively discouraged or forbade ceremonial dances, feasts, and other gatherings, fearing that they might unite tribes or keep them from assimilating into white culture. Most gatherings required written permission. One explanation for the Indian Bureau allowing celebrations at all was offered in Sunday Magazine (July 2, 1911): “Shut off on reservations and compelled to do without any extraneous amusements, the Indian grows morose and is much more inclined to give trouble than when occasionally permitted to enjoy himself.”

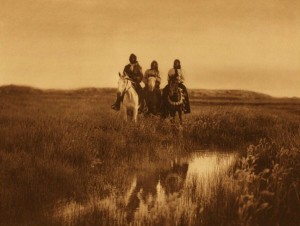

The Bureau didn’t pay as much attention to Fourth of July celebrations, and Native Americans soon discovered that they could get together on that day without written permission. They began to use the Fourth of July as an excuse to gather and perform the dances and ceremonies they enjoyed. Some tribes had a practice of giving away assets during celebrations, often through a formal ceremony called a potlatch. Native Americans considered it an honor to give their possessions to others, and often gave to the poorest members of the tribe, first. Sioux Indians apparently ramped up this gift-giving practice on the Fourth of July, and the Indian Bureau began calling this “Give-Away Day.” Tribal members celebrated the Fourth with games of skill and strength, feasting, and dancing. They also incorporated their practice of honoring individuals with important gifts, with no thought of reciprocation. Gifts were substantial–horses, fancy bead work, saddles, and other valuable items. Whites seemed to be amazed by the practice, since it often left the giver without any resources.

______________________________________________________________________________________