State insane asylums are usually thought to be a little (or a lot) worse than private institutions, and that is probably true in many cases. Private asylums had a bit more freedom in accepting patients and in hiring staff, and that was often reflected in the their general atmosphere and the treatment of patients. However, private institutions could have their own problems. Continue reading

Tag Archives: McLean Asylum for the Insane

Sharp Contrasts

Much of the commentary concerning insane asylums tends toward the negative, and rightly so, since they were often places of confinement for people who were in them unwillingly. Treatments were also much too vigorous at times, and many patients must have felt a pervasive sense of potential violence within the institution. Continue reading

Make it Pretty

Occupational therapy was an important part of patient care in nearly all asylums. Patients were encouraged to do skilled work that got their minds off their problems/issues and produced a tangible object in which they could take pride. Genteel ladies might do fancy sewing while men engaged in woodwork, even in an elite asylum such as the McLean Asylum for the Insane in Massachusetts.

Indian patients at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians were also encouraged to do crafts like beadwork and basket weaving if they so desired, to help pass time. (Peter Thompson Good Boy spent time “beading” at St. Elizabeths during his stay there beginning in 1913.) Occasionally, patients like Lizzie Vipont earned a little bit of money with their beadwork by selling items to visitors. Necklaces and handbags seemed to be most popular–or at least are mentioned most often. One report mentions that men whittled wooden objects, but went on to say that women were the primarily crafters. The asylum’s second superintendent, Dr. Harry Hummer, also allowed these kinds of occupations, but apparently stopped encouraging it so that the practice fell by the wayside.

This photo appeared in USA Today. Artifacts left over from the Hiawatha Insane Asylum for Indians in Canton, S.D. are displayed at the Canton Public Library on April 23, 2013. Photo: Elisha Page, Sioux Falls, S.D. Argus Leader

The Luxury of Time

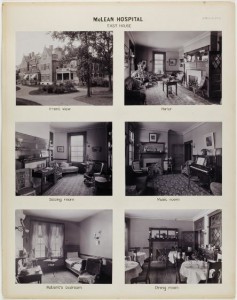

The wealthy at McLean Asylum for the Insane enjoyed many amenities that less affluent patients did not (see last post). Some patients lived in single-dwelling cottages with several bedrooms, a dining and living room, modern bathrooms, and sometimes even servants’ quarters. Typically, these cottages were paid for by the patient’s family and later deeded to McLean, in exchange for the relative’s care. Though many patients appreciated their surroundings, what they and their families benefited most from was the time that their alienists and physicians could give them.

Doctors caring for a wealthy patient had the time to give detailed instructions on how a particular person was to be treated; for instance, one patient’s entry stated that she could come and go from her cottage as she pleased, read whenever she wanted, and shampoo her own hair when it suited her. Alienists at McLean could take their time with patients’ histories, noting what pleased and displeased them, what might have caused the onset of their disorder, how they reacted to certain situations, etc. More than that, the nursing and attendant staff were not so hurried and harried. They could accompany patients on leisurely walks, talk to them and assist them in numerous ways, and retain the patience and kindness that other hospitals drove out of its staff by overwork. Many of McLean’s patients undoubtedly were helped simply by the respectful treatment they received.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Wealth Has Its Privileges

Room in a Cottage for Women at Michigan Asylum for the Insane, circa 1891, courtesy kalamazoo public library

The great majority of insane asylum superintendents did not set out to be deliberately cruel to patients. They understood that newcomers to the institution would be frightened and/or confused, and made an effort to meet new patients as soon as as possible so they could welcome and reassure them. Even when asylums grew too large to permit this, superintendents and staff looked at ways to make their asylum more homey and comforting. Some set up cottages or separate buildings where the number of patients could be kept small, or moved patients to wards where similar patients stayed. Quiet or reserved patients would therefore stay with others like themselves (no matter what brought on their condition) versus mixing with loud and/or violent patients who perhaps had the same complaint as theirs.

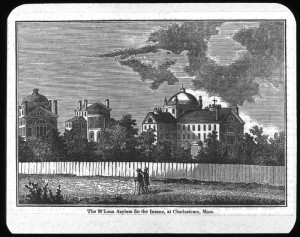

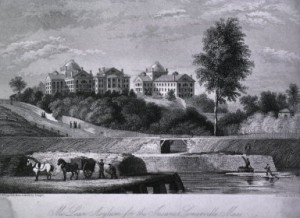

As always, money made a difference. Wealthy families could often keep their family members at home, cared for by a private nurse or attendant. However, if the patient grew too violent or uncontrollable, even wealthy families might find it better to take their loved one to an asylum. The majority of asylums were state-run, and took patients at low-income levels; however, a few asylums catered to paying clientele. The McLean Asylum for the Insane was such an asylum, and its lush accommodations began with its exterior. Rain gutters were copper, views were spectacular, and the golf course was ready for play.

My next post will describe McLean further.

Frederic Packard, a Member of McLean's Staff and Later Superintendent, circa 1920, courtesy harvard.edu

______________________________________________________________________________________

Many Kinds of Cruelty

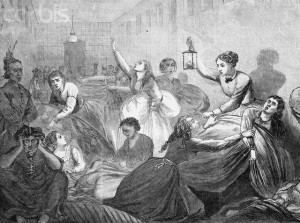

One of the worst kinds of abuse patients at insane asylums suffered occurred simply because of the situation. Many patients were tricked into accompanying relatives or friends to an asylum, or to a sanity commission that had been convened to arrange for commitment. Elizabeth Stone recounted her own commitment as this kind of deception. Her brother asked her to take a ride with him and conveyed her to McLean Asylum , where he abruptly left her without telling her where she was and what was going on. Stone was distressed beyond words when she finally realized what had happened, and later wrote: “O! That a dagger had been plunged into my heart in the midnight hour!”

Once in an asylum, many patients were frightened, angry, and bewildered. Many were distraught and emotionally overwhelmed by a sense of betrayal and shock at what had occurred. Women from sheltered homes were often terrified by the chaos around them. Patient accounts speak of real fear–of both patients and doctors whom they did not trust–and fear that they would never be released. Some learned to adapt and become model patients, hoping that by exhibiting desirable behavior, they might be set free. For far too many, the trip to the asylum was the last trip they would every make. By the time family members committed a person to an asylum, they were generally ready to be rid of him or her for a very long time.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Long Distance Oversight

Few people ever wanted to enter an insane asylum, no matter how well run or up-to-date it was. And, like all institutions run by fallible human beings, asylums were not immune to mistakes and misjudgments on the part of their staffs. One problem the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians faced that St. Elizabeths and McLean didn’t (see last few posts) came as direct consequence of its long-distance oversight.

The Canton Asylum for Insane Indians was not under a trustee or board of visitors system like the other two asylums, though it is certainly untrue that this establishment was never inspected or investigated. However, the asylum was managed for the most part from thousands of miles away. The asylum’s superintendent in Canton reported directly to the commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington, DC, and the seven commissioners who held the position during the time the asylum was open very seldom, if ever, actually visited the place.

Agents or inspectors from the Indian Office did come by fairly regularly, but none of these men were psychiatrists. They found it difficult to determine how well the patients were being treated for mental health issues, and usually confined themselves to commenting on the state of the buildings and how efficiently the superintendent ran his farming operation. Medical staff from the Indian Office eventually began visiting much more often as the asylum grew in size and came to the notice of the commissioner through complaints. Dr. Emil Krulish became a frequent visitor and made numerous criticisms that honed in on treatment and the way the superintendent, Dr. Harry Hummer, managed his personnel and patients. However, his voice was ignored and Hummer continued to thrive in his position.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Overlooked

McLean Asylum for the Insane and St. Elizabeths were two very different, yet for the most part, well-regulated insane asylums (see last two posts). And though they differed from each other in terms of funding and client base, they contrasted even more sharply with the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians. The Canton asylum was a government-funded asylum like St. Elizabeths, and both of these institutions focused on either indigent patients or those of moderate income. What really set the Canton asylum apart from McLean and St. Elizabeths, though, was the difference in oversight.

At McLean, trustees watched over the management of the asylum and a Visiting Committee “made it a point to see personally each patient in the asylum once a week, checking his name off a prepared list,” according to the editors of The Institutional Care of the Insane in the U.S.A. and Canada, published in 1916. This extraordinary degree of oversight took place well before 1900, when the facility had one nurse for every four patients. As the asylum grew, trustees could not keep to the same schedule, but they were still intensely involved with the asylum. Even at the turn of the twentieth century, trustees hired eminent architects for additional buildings, and doctors knew their patients and kept detailed histories on them.

The government hospital, St. Elizabeths, first fell under the scrutiny of a five-member board of charities, appointed by the President of the United States for terms of three years. Additionally, the President appointed a nine-member Board of Visitors. This board included representatives of the military and clergy, and many times included an acting or retired surgeon-general. In 1914, Brigadier General George M. Sternberg, a pioneer in battlefield wound treatment during the Civil War, was President of the Board, and the surgeon generals of the Navy and Army were also represented. The latter surgeon-general was William C. Gorgas, who had been responsible for wiping out yellow fever in Havana after Walter Reed’s discovery of the mosquito vector for it. Though St. Elizabeths had its share of detractors and investigations, that asylum and McLean were typically watched over by prominent locals who took their duties seriously and felt responsible for providing area patients with quality care.

In my next post, I will discuss oversight for the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians.

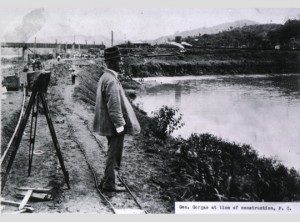

William C. Gorgas at the Time of the Panama Canal Construction, courtesy National Library of Medicine

______________________________________________________________________________________

Another Contrast

It perhaps isn’t quite fair to compare a federal insane asylum like the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians with a private institution catering to the wealthy. (See last post about McLean Asylum for the Insane.) However, the government did have another insane asylum, and it was also quite different from the one at Canton. St. Elizabeths had a training school for nurses, quarantine rooms, and a full hospital where operations ranging from appendectomies to hysterectomies were performed. It was one of the first asylums in the country to appoint a pathologist to its staff, and one of the first to institute therapeutic hydrotherapy.

At about the time that the Canton asylum opened, Dr. William A. White arrived at St. Elizabeths. He created a clinical director position, and organized a scientific department which eventually included a pathologist, psychologist, histopathologist, and a number of assistants. The department published their research in the form of an annual bulletin. St. Elizabeths also trained surgeons from the Public Health Service and Marine Hospital Service to work on Ellis Island (helping discover insane immigrants). The hospital shared its research with the U.S. Army and Navy to help bring military psychiatry into their respective branches. The Canton Asylum for Insane Indians was much smaller than St. Elizabeths and perhaps couldn’t be expected to do the same things. However, its staff could have done much more research on mental health issues in a unique population than it did, and been much more involved with its peer organizations that it was. Instead, the asylum’s most significant staff member, Dr. Harry Hummer, allowed the facility to stagnate into a backwater institution that helped its patients very little.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Opposing Systems

Though Dr. Harry R. Hummer’s medical and psychological experience did not guarantee the best care for patients at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, at least he had the proper background for the position he held. The asylum’s first superintendent, Oscar Gifford, had no medical training at all. The Indian Office bears exceptional fault for appointing someone without the obvious qualifications to head a medical facility; by 1902, it was nearly incomprehensible that an insane asylum superintendent would not also have a psychiatric background.

In contrast, the McLean Asylum for the Insane in Massachusetts was a premier establishment that catered to wealthy families who could afford to give their loved ones the best of care. Its staff administered typical therapies for the time: calomel, Epsom salts, opium products, and various purges, along with rest and recreation designed to calm patients and help them keep their minds off their troubles. Recreation could include sewing and reading, billiards, tennis, strolls through manicured gardens, carriage rides, trips into town, and art appreciation classes. But, despite its country club atmosphere, between 1888 and 1892, McLean established laboratories that combined biological chemistry, physiological psychology, and psychiatry, and were perhaps rivaled by only Professor Emil Kraepelin’s laboratory in Heidelberg, Germany.

______________________________________________________________________________________