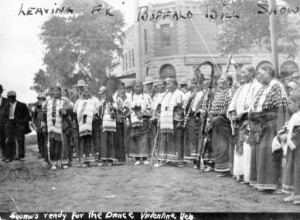

White society saw Native American dancing in two ways: immoral and/or depraved, or as perfectly acceptable cultural expression (see last two posts). Native Americans often pointed out that their dances were not as immoral as white dancing, which included close physical contact as well as uninhibited movements. Continue reading

Tag Archives: John Collier

Duking it Out

Few townspeople liked Dr. Harry Hummer when he first came to Canton, primarily because he was replacing the very popular former superintendent of the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, Oscar Gifford. However, Hummer eventually began to fit in and the Canton community stood shoulder-to-shoulder with him when the asylum was threatened with closure. Continue reading

Dancing Controversy

Native American dancing caused controversy for several reasons (see last post). Missionaries saw paganism or sexual immorality in dancing, and also considered it a hindrance to their efforts to convert Indians to Christianity; the Indian Office felt that traditional dancing impeded Indians’ assimilation into white culture. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Charles Burke, had threatened action if dancing wasn’t sharply curtailed, and this was no idle threat. The Religious Crimes Code of 1883 gave agency superintendents authority to use force or imprisonment to stop practices they felt were immoral, subversive, or counter to government assimilation policies. Though all Native American dancing was denounced, government attention and a great deal of controversy eventually centered on the Pueblos and their dances.

By the time Burke issued his directives against dancing (Circular No. 1665 and its supplement) in 1921 and 1923, the changing times brought a bit of opposition he hadn’t anticipated. By the 1920s, a group of reformers, intellectuals, artists, and other non-traditionalists had begun to support Native American culture. They pushed back against Burke and others with an assimilation agenda, and eventually drummed up enough publicity and legal opposition to defeat some of the more outrageous demands of whites in power. They particularly used the guarantees of religious freedom as a weapon to defend native culture; both Pueblos and their white supporters emphasized that dancing was part of Native American religious ceremonies.

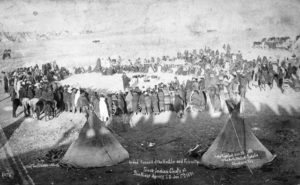

As time went on and more liberal views of Native American culture emerged in Congress, Burke and others of like mind began to lose power. Former Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Collier, writing in his memoir, From Every Zenith, described a visit to a Navajo reservation in the late 1920s. During that visit, two senators, a government attorney, and the assistant commissioner of Indian Affairs, J. Henry Scattergood, danced the squaw dance with the unmarried Navajo girls.

______________________________________________________________________________________

This Land is My Land

White Americans often seemed to feel that Indian land was available for their own needs. In 1927, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Charles Burke, met with the Montana Power Company and white farmers to discuss a water project. They proposed to use land belonging to the Flathead Indians to build a water power site to create inexpensive electricity, but failed to invite Flathead Indians to the meeting. Representative Louis C. Cramton (chairman of the House Appropriations Subcommittee for the Interior Department) favored the action because it would help white settlers “hanging on by their fingertips . . . to share in the national prosperity.”

Activist John Collier and several powerful senators opposed the bill, saying it was detrimental to Indian interests. Collier wrote to President Coolidge to ask him to intervene in the Flathead project, but Coolidge never wrote back. Nevertheless, Congress defeated the bill, and in 1928, passed a bill that acknowledged Indian ownership of the rentals from the water project.

___________________________________________________________________

Hummer’s Advantages

At the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, superintendent Dr. Harry R. Hummer was far enough away from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to avoid direct supervision. Hummer outlasted five commissioners: Francis Leupp, Robert Valentine, Cato Sells, Charles Burke, and Charles Rhoads before commissioner John Collier threw him out of the asylum and the Indian Service.

One advantage Hummer had–as did other superintendents elsewhere–was that locals wanted the asylum to remain open and running. Insane asylums represented huge boosts to local economies. Most towns or cities where asylums were located were quite happy about having them, and were proud of the work they did. Canton was no different. Locals enjoyed the employment and local contracts that came from the asylum and usually spoke of it quite enthusiastically.

When Hummer began to finally receive less than glowing reports, he managed to have some friends in Sioux Falls appointed as an inspection committee. They came through for him in a report to Commissioner Charles Burke early in 1929. “We went through the plant thoroughly from top to bottom and . . . found everything in first class condition.” The writer then concluded, “I consider Dr. Harry Hummer a wonderful superintendent of this institution and he has many fine employees.”

______________________________________________________________________________________

How Does the Bureau of Indian Affairs Run?

John Collier’s article about Amerindians (see last post) laid the blame for much of the Indians’ misery on the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Indians were now full citizens of the United States, Collier wrote, but unlike all other citizens, were completely under the control of Congress through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The BIA controlled Indian property valued at $1,650,000,000, Indian income, and even their persons to a great extent.

The BIA could force Indian children to go to schools hundreds of miles away from home, “enforce an unpublished penal code” that allowed them to arrest Indians at will, censor Indians’ religious observances, and nullify an Indian’s last will and testament unless it had been previously approved by the BIA.

Worst of all, said Collier, the BIA “makes accounting to no agency juristic, legislative, and administrative.” It acted as a government unto itself and had a monopoly of control on reservations. He did note that the agency was finally having to account for itself through a survey being conducted at the time of his writing. This accounting resulted in the Meriam Report, discussed in posts on May 12-19.

________________________________________________________________________

The Dismal State of American Indians

John Collier wrote an article in 1929, entitled “Amerindians,” which used measured language and concrete statistics to paint a sober picture of American Indians’ well-being. According to Collier’s figures, the number of Indians who lived in the U.S. had fallen from approximately 825,000 at the time of America’s discovery by Europeans, to 350,000 at the time of his writing.

Day school was mandated for children aged six to eighteen, and they had to go to boarding schools away from their families if there were no acceptable schools nearby. Collier noted that “the food allowance for the children is eleven cents a day, supplemented in a few cases by provender from school gardens and dairies.”

The 1925 census showed a 62% increase (28.5 per 1,000) in the death rate of Indians over the previous five years. This figure showed that the Indians’ death rate had surpassed their birth rate. The Bureau of Indian Affairs disputed the census findings, but according to the article, admitted that the Indian death rate was about 95% higher than the general death rate.

________________________________________________________________________