White society saw Native American dancing in two ways: immoral and/or depraved, or as perfectly acceptable cultural expression (see last two posts). Native Americans often pointed out that their dances were not as immoral as white dancing, which included close physical contact as well as uninhibited movements. Continue reading

Tag Archives: Indian dance controversy

Why All the Concern?

The controversy over Native American dancing did not arise all at once, of course (see last post). European settlers were often surprised at the energy and freedom inherent in many ceremonial dances, but unfortunately attributed much of it to the “uncivilized” status of Native Americans. Continue reading

Dancing Controversy

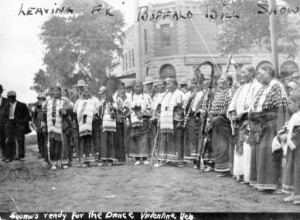

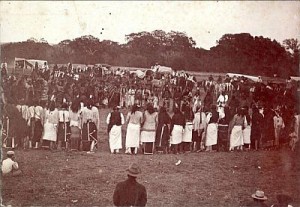

Native American dancing caused controversy for several reasons (see last post). Missionaries saw paganism or sexual immorality in dancing, and also considered it a hindrance to their efforts to convert Indians to Christianity; the Indian Office felt that traditional dancing impeded Indians’ assimilation into white culture. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Charles Burke, had threatened action if dancing wasn’t sharply curtailed, and this was no idle threat. The Religious Crimes Code of 1883 gave agency superintendents authority to use force or imprisonment to stop practices they felt were immoral, subversive, or counter to government assimilation policies. Though all Native American dancing was denounced, government attention and a great deal of controversy eventually centered on the Pueblos and their dances.

By the time Burke issued his directives against dancing (Circular No. 1665 and its supplement) in 1921 and 1923, the changing times brought a bit of opposition he hadn’t anticipated. By the 1920s, a group of reformers, intellectuals, artists, and other non-traditionalists had begun to support Native American culture. They pushed back against Burke and others with an assimilation agenda, and eventually drummed up enough publicity and legal opposition to defeat some of the more outrageous demands of whites in power. They particularly used the guarantees of religious freedom as a weapon to defend native culture; both Pueblos and their white supporters emphasized that dancing was part of Native American religious ceremonies.

As time went on and more liberal views of Native American culture emerged in Congress, Burke and others of like mind began to lose power. Former Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Collier, writing in his memoir, From Every Zenith, described a visit to a Navajo reservation in the late 1920s. During that visit, two senators, a government attorney, and the assistant commissioner of Indian Affairs, J. Henry Scattergood, danced the squaw dance with the unmarried Navajo girls.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Dancing and Morals

Missionaries trying to convert Native Americans to Christianity took particular exception to the traditional dances of native peoples. Some Christian denominations considered dancing immoral for anyone–whites included–but even denominations that might have tolerated a lively square dance typically found Native American dancing somewhat shocking. Whether it was the sometimes scanty apparel of participants, the exuberance of certain dances, or simple unfamiliarity on their part, missionaries often lumped all their objections into a universal condemnation. Native American dances were “degrading” in their eyes.

The Indian Office frequently backed missionaries in their assessments of Indian culture, and certainly did in this case. In the 1920s, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Charles Burke, issued two directives against dancing: Circular No. 1665, Indian Dancing (1921), and a supplement to it two years later. Eventually, the dancing controversy centered upon the Pueblos. They, as well as white supporters, contended that their dances were part of their religion and should be protected, while missionaries and supporters of assimilation argued that the dances were merely pagan rituals. The resulting clash over religious rights eventually sent a powerful message to the Indian Office.

My next post will further discuss the dancing controversy.

______________________________________________________________________________________