Because it was more cost-effective to house many patients rather than a few, insane asylums tended to grow larger and house more patients over time. Dr. Harry Hummer of the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians felt his disadvantage in numbers very keenly. He strove continually to find ways to cut costs, and to increase his number of patients. The latter required an increased capacity for his institution, which Congress did not necessarily support. Hummer repeatedly made a case for more buildings, more farmland, and more patient beds.

Though no one ever conclusively settled the question of whether or not Indians had as much, more, or less insanity than whites, statistics about the growing number of insane were on Hummer’s side. The various states had compiled statistics on the number of insane for many years, and the rate per 100,000 rose steadily each decade of the census. In 1840, 50.7/100,000 of the population were reported as mentally ill, while 169.7/100,000 were reported so by 1890.

The number of insane in hospitals (all races) had risen to 252.8/100,000 by 1920, though the census also shows that Indian hospitalization was only 104.5/100,000. The figures for Native Americans may have been skewed due to a lack of access to mental health care, or lack of room at state mental institutions or at the Canton Asylum. The Native American population stood at 244,437 in 1920. Even with their remarkably low rate of hospitalization for insanity (it was 259.8 for whites) Hummer could have conservatively estimated the number of insane Indians to be around 250. In 1920, Hummer had only 86 patients.

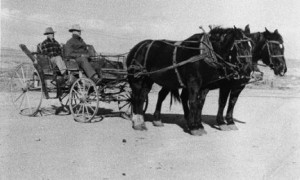

Patients Working in Fields at Western North Carolina Insane Asylum, courtesy Western Piedmont Community College

______________________________________________________________________________________