Alienists’ assessments of their patients’ mental conditions could be suspect at the best of times. They were particularly suspect when alienists dealt with people who did not fit the norms of an Anglo-centric society. Newly arrived immigrants were vulnerable to a misinterpretation of their mental status, and of course, non-English speaking Native Americans could easily be misunderstood or be so frustrated and frightened that they couldn’t communicate effectively. Continue reading

Tag Archives: Blackwell’s Island

Employee Frustration

Employees at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians didn’t always get along, and the institution’s first big inspection proved that. Dr. Turner had a beef with superintendent Gifford (see last post), but some employees had a beef with Turner.

One attendant in particular, Mary J. Smith, found her work difficult in part because of Turner’s instructions. He did not like to use restraints and wouldn’t often authorize them, but Smith said that she couldn’t do all of her work unless she locked certain patients in their rooms. Her 1908 affidavit stated:

“Doctor had forbidden her to lock certain patients up without his permission . . . ‘he told me if I was doing my duty I would have her (Mary LeBeaux) outside instead of locked in her room, at that time I had locked her in for throwing a cuspidor at me’.” The inspector taking the statement said that “she has marks on her body where the patient has bitten her and has thrown cuspidors at her repeatedly.”

This kind of situation was a quandary for attendants at all asylums: how to handle violent patients without resorting to restraints or reciprical violence. One solution was to call in enough attendants so that the patient could be safely restrained by humans until he/she calmed down. Unfortunately, Canton Asylum had too few attendants for this to be a feasible solution.

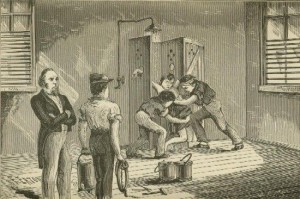

Woman Forced Into Cold Shower, from Elizabeth Packard's book Modern Persecution, or Asylums Revealed

______________________________________________________________________________________

Meals at Asylums

The quality of food at asylums ranged from the piece of bread and five prunes Nelly Bly received on Blackwell’s Island to the abundance of milk and eggs sickly patients received at St. Elizabeths. Many institutions made a point of offering enticing food to patients who had problems eating; one woman at Hilltop recounted the generous breakfast of oatmeal, bacon, scrambled eggs, toast, milk and juice, and the evening pot of chocolate brought to her by staff.

Physicians generally considered it positive when patients put on weight. Notes on a woman named Katie at the Southwestern Lunatic Asylum in Virginia said that she had “fattened up some.” Of another woman there, the physician wrote that she had “gained flesh and strength.” Of others, doctors noted that patients had “improved in flesh” or had “grown stout.” There never seemed to be any attempts to help patients lose weight, even if they were described as “quite stout.”

The superintendent at Southwestern Lunatic Asylum, Harvey Black, wrote in his first report that three things were necessary to help patients recover and go home: a sufficient quantity and variety of good food, neat, comfortable clothing, and a sufficient number of efficient ward attendants. He spoke of a planned orchard of 400 apple trees, peach and pear trees, grapes, and berries, and stated that even more than that was needed. If nourishing food did have curative powers, Black seemed to want to provide it.

______________________________________________________________________________________

A Growing Population of the Insane

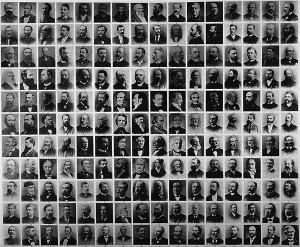

In 1844, thirteen superintendents of insane asylums met to exchange ideas about how to best run institutions for the insane. From this meeting, they formed the Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane (AMSAII). As recognized experts in a very young field, they felt themselves the top authority on all matters concerning mental disease. Some of the superintendents were somewhat arrogant, but were undoubtedly sincere and enthusiastic.

In 1844, the Association proposed some ground rules for asylums. Among other propositions, they agreed that asylums should be in the country, but easily accessible from a large town. Each site should have about 50 acres of landscaped grounds besides other acreage for its needs. Superintendents felt strongly that no building should hold more than 200 patients, and only 250 at the very most. In 1866, they increased that acceptable number to 600. The original members would have been shocked to find how quickly overcrowding became one of the worst features of asylums, with sometimes thousands of patients crammed together in filth and disorder.

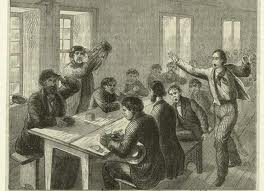

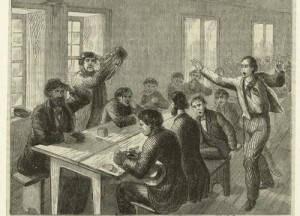

Unruly Patients at Blackwell's Island, from Harper's Magazine, 1860, courtesy New York Public Library

______________________________________________________________________________________

Lunatic Balls

As part of their treatment, patients in insane asylums were sometimes allowed recreational opportunities. The New York Times (1874) described an annual ball at the New-Haven, Connecticut lunatic asylum with typical 19th century indifference to patients’ feelings:

“Twenty couples entered the hall, ranged in two lines facing each other, and stood still in profound silence, waiting the music. In this party the strangeness of the performers was most apparent. […]The music burst forth and a simultaneous movement followed; all sorts of movements, some cultivated steps, but for the most part a mere violent shuffling exercise. Directly they all seemed to have forgotten that they had partners, and settled down into dancing. There was some peculiarity about every individual, but in every one was observable a sort of ecstacy [sic].”

A description of a fire at Blackwell’s Island City Lunatic Asylum in 1879 also referenced lunatic dancing. When an alarm sounded and patients were released from their cells:

“To allay their fears, and to quiet the excitement which many of them began to exhibit owing to their being disturbed at an unusual time, the lunatics were told were told that there was to be a dance in the Amusement Hall. […]A merry air was played on the piano, and in a few minutes the lunatics were dancing and capering about in high glee.”