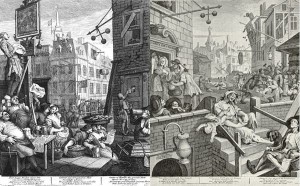

William Hogarth, a British artist born in 1697, became well known for both his satirical and morality engravings and paintings. During the 1730s and 1740s, Hogarth became interested in social and moral causes. He used his considerable talents to illustrate the sorrowful lives of those in poverty or who became impoverished due to poor choices. He took on crime, gambling, prostitution, drinking, and greed, making his moral points through intricate scenes that needed little explanation.

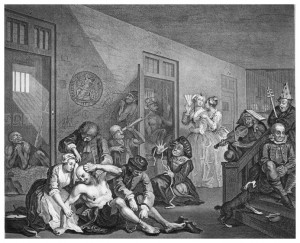

One of Hogarth’s best-known works is a series of paintings called “A Rake’s Progress,” which follows a young man who inherits a fortune from his miserly father. He becomes a fashionable gentleman, drinks to excess and lives riotously, and eventually squanders his wealth. After various trials and tribulations of his own making, the no-longer-young Tom Rakewell ends up in the madhouse at Bedlam. Hogarth captures the misery of the institution during its days of poor treatment for patients.

______________________________________________________________________________________