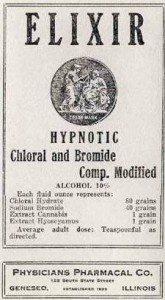

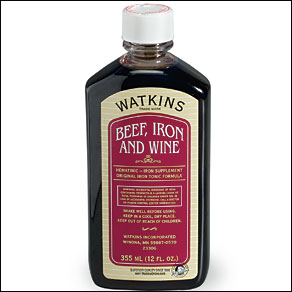

Patients who came in malnourished or otherwise neglected often needed building up. However, doctors often had plenty of patients that they needed to settle down rather than energize. Sedatives like bromides (usually potassium or sodium bromide) were very popular for excitable patients.

Many patients at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians were epileptics. Sodium bromide and potassium bromide were also used as anti-seizure medicines. At the time, bromides had a secondary (though related) use. Many doctors thought epilepsy was caused by masturbation, and the drug calmed sexual excitement. There is no evidence that any of the doctors at Canton Asylum believed this theory, but they did rely heavily on bromides for their epileptic patients.

Bromide doses were difficult to adjust, since the drug stayed in the body a long time. Chronic overdoses could lead to a toxic condition called bromism, which itself presented neurological and psychiatric symptoms like confusion, emotional instability, hallucinations, and psychotic behavior.

________________________________________________________