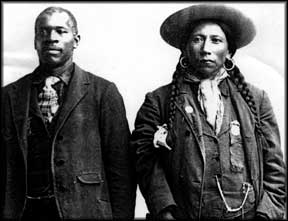

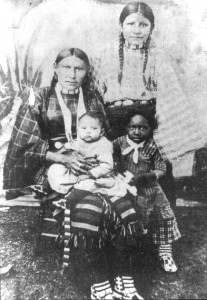

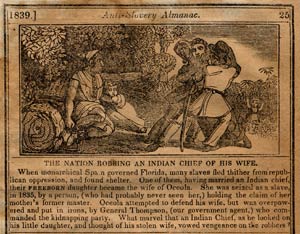

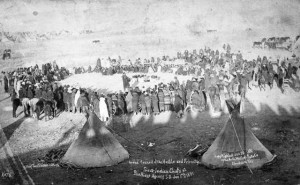

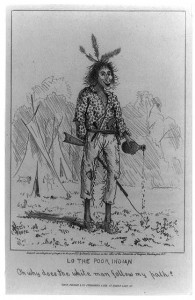

Native Americans in the Five Civilized Tribes sometimes owned African slaves. The Cherokee freed their slaves in 1866 and gave them full tribal citizenship. These former slaves were called tribal Freedmen.

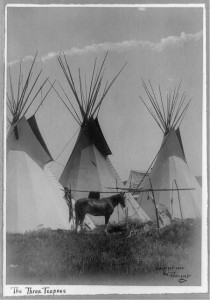

Many Freedmen lived as Native Americans through the ensuing years, having adopted their culture and languages.

Today, Freedmen face roadblocks in tribal enrollment, since proving their bloodline depends upon the 1906 census called the Dawes Roll, which excluded Freedmen. This proof of bloodline is very important, since it is required to qualify for a Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood. The CDIB and tribal membership entitles the holder to Native American monies and benefits.

________________________________________________________